While 2020 can be said to have been a total disaster of a year in so many ways, I am happy to offer up one very exciting, positive, and downright awesome accomplishment: William Cowper is back home at Chawton House.

Now, Cowper was not aware he had been sent from home at some point, but in the history of the whys and wherefores of the books in Edward Austen Knight’s library at Godmersham Park, i.e. why some remained and some were sold, the fact that William Cowper’s Poems left the nest was a sad event, and the finding and returning of it has really been the Holy Grail of our team of diligent GLOSSers. And so we are Happy to report that the deed is done, this Holy Grail of ours now in the safekeeping of the Library at Chawton, and we can all rest easy from here on in.

You can read the Chawton House announcement here: https://chawtonhouse.org/2021/01/treasured-austen-family-heirloom-returns-home/

[UPDATE: Here is a photo in The Times of January 4, 2021, with Chawton House’s Clio O’Sullivan proudly holding up the Cowper for all the world to see – excellent PR!]

**************

What was different about this particular book is that it has been available since the Reading with Austen project began – for sale at Bernard Quaritch and completely out of our reach. And every time we found ourselves getting closer, another GPL book would show up at auction, and off went our scant funds to purchase it. Enter the Friends of the National Libraries! To their very generous donation to Chawton House for the express purpose of acquiring this Cowper, GLOSS was able to supply the needed additional funds, and the Cowper is now officially at Chawton once again.

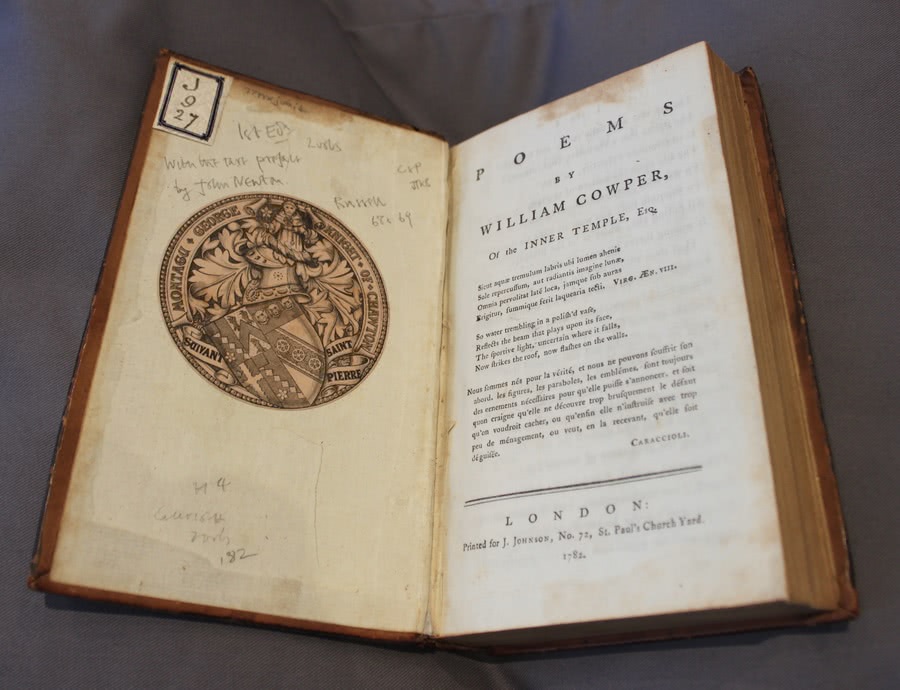

The title itself is actually two volumes of poems: the first one published in 1782 was Cowper’s first published work Poems, by William Cowper, of the Inner Temple, Esq. (J. Johnson, 1782)

Title Page, Poems, 1782, RwA website

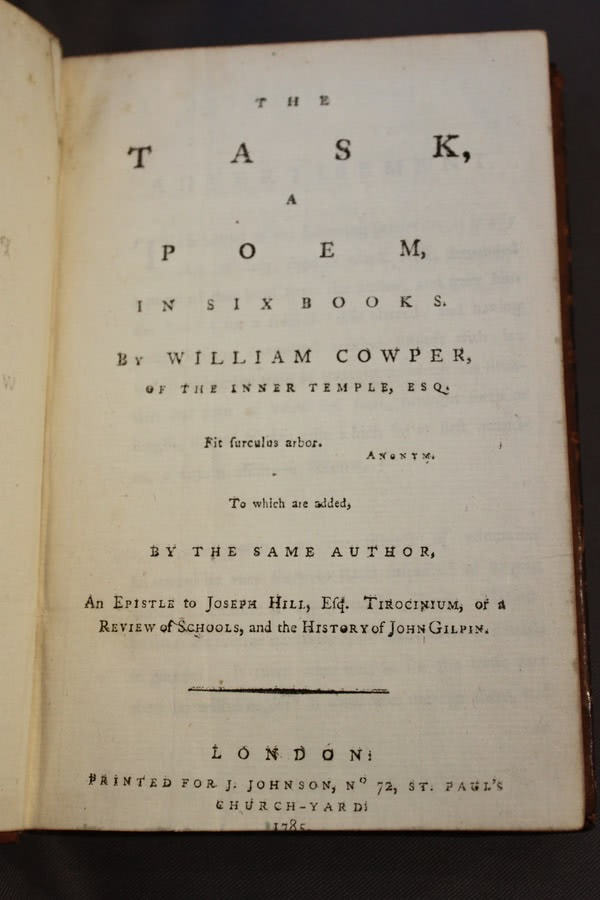

The second volume is the 1785 published edition of Cowper’s most well-known poem The Task, A Poem in Six Books, to which is added his comic poem “The Diverting History of John Gilpin.” (Johnson, 1785)

Title page, The Task (1785), RwA website

So why William Cowper? What makes this book so important to The Reading with Austen project and the Library at Chawton House?

Does anyone actually read him anymore? Does anyone actually know how to properly pronounce his name?? [it’s Cooper]. Does he perhaps have something to do with Jane Austen??

Well, it all started with Henry Austen – in his “Biographical Notice” in the posthumous publication of his sister’s Northanger Abbey and Persuasion, he writes:

Her reading was very extensive in history and belles lettres; and her memory extremely tenacious. Her favourite moral writers were Johnson in prose, and Cowper in verse.

This then was a ready invitation to find Cowper reflected in all her letters and all her fiction – and one is not disappointed:

- In November 1798 [Ltr. 12], Austen writes to Cassandra:

We have got Boswell’s “Tour to the Hebrides’, and we are to have ‘his Life of Johnson’; and, as some money will yet remain in Burdon’s [the bookseller] hands, it is to laid out in the purchase of Cowper’s works.

[Deirdre Le Faye suggests that this would either be the 6th edition of 1797 or the new edition of 1798]. Ed. I believe that the 6th ed. was published in 1794, so a typo, a later printing of the 6th or a later edition??…. shall look into this…

2. And nearly a month later in December 1798 [Ltr. 14], she writes again that “My father reads Cowper to us in the evening, to which I listen when I can.”

3. When next Austen mentions Cowper, in February of 1807, we can readily believe she has memorized all of his poetry, because she drops his lines whenever she can, and it is the Sharp Elves eyes of many an Austen scholar who have found these gems:

Now in Southampton, Austen writes of the Shrubs which border the gravel walk in her garden: “…we mean to get a few of the better kind & at my own particular desire he procures us some Syringas. I could not do without of a Syringa, for the sake of Cowper’s Line. – We talk also of a Laburnam [sic].” [Ltr. 50]

Cowper’s line: from The Task “The Winter Walk at Noon”

‘…Laburnum, rich / In streaming gold; syringa, iv’ry pure.’

************

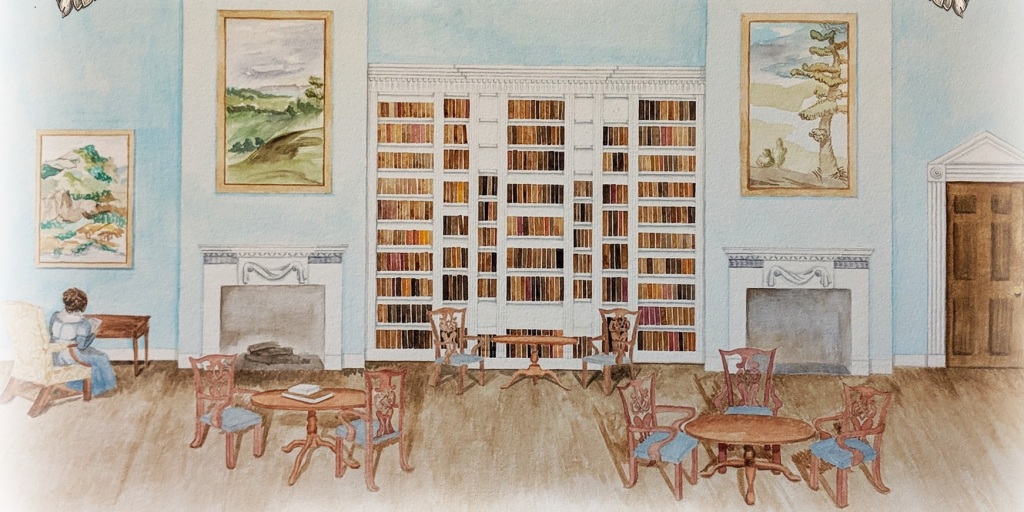

4. In September 1813, Austen is at Godmersham, and we can perhaps imagine she has this very Cowper in hand when she writes:

“I am now alone in the Library, Mistress of all I survey – at least I may say so & repeat the whole poem if I like, without offence to anybody.” [Ltr. 89]

Here Austen is playing on Cowper’s words in his “Verses, supposed to be written by Alexander Selkirk” where we find:

“I am monarch of all survey,

My right there is none to dispute;

From the centre all round to the sea,

I am lord of the fowl and the brute.”

[You can read the full poem here: https://www.eighteenthcenturypoetry.org/works/o3794-w0130.shtml and we can only imagine Austen sitting there in the Godmersham Park library, reciting this aloud to herself!]

5. In November of the same year, and again at Godmersham, Austen writes of Henry’s man-servant William, who apparently is a lover of the country rather than of city life: “An inclination for the Country is a venial fault. – He has more of Cowper than of Johnson in him, fonder of Tame Hares & Blank verse than of the full tide of human Existence at Charing Cross.” [Ltr. 95]

Cowper writes in concluding “The Sofa”:

God made the country, and man made the town.

What wonder then, that health and virtue, gifts

That can alone make sweet the bitter draught

That life holds out to all, should most abound

And least be threaten’d in the fields and groves?

Possess ye therefore, ye who, borne about

In chariots and sedans, know no fatigue

But that of idleness, and taste no scenes

But such as art contrives, possess ye still

Your element; there only ye can shine,

There only minds like yours can do no harm.

Our groves were planted to console at noon

The pensive wand’rer in their shades. At eve

The moon-beam, sliding softly in between

The sleeping leaves, is all the light they wish,

Birds warbling all the music. We can spare

The splendour of your lamps, they but eclipse

Our softer satellite. Your songs confound

Our more harmonious notes: the thrush departs

Scar’d, and th’ offended nightingale is mute.

There is a public mischief in your mirth,

It plagues your country. Folly such as your’s,

Grac’d with a sword, and worthier of a fan,

Has made, which enemies could ne’er have done,

Our arch of empire, steadfast but for you,

A mutilated structure, soon to fall.

*******************

Now for the Novels:

- First, in Sense and Sensibility, Marianne bemoans Edward’s appalling lack of emotive reading skills:

“Oh! mama, how spiritless, how tame was Edward’s manner in reading to us last night! …To hear those beautiful lines which have frequently almost driven me wild, pronounced with such impenetrable calmness, such dreadful indifference!-

“He would certainly have done more justice to simple and elegant prose. I thought so at the time, but you would give him Cowper.”

“Nay, mama, if he is not to be animated by Cowper! – but we must allow for differences of taste…but it would have broke my heart had I loved him, to hear him read with so little sensibility.” [S&S, Vol. I, ch. 3]

And later, from Elinor:

“Well, Marianne…you have already ascertained Mr. Willoughby’s opinion in almost every matter of importance. You know what he thinks of Cowper and Scott; you are certain of his estimating their beauties as he ought, and you have received every assurance of his admiring Pope no more than is proper.” [S&S, Vol. I, ch. 10]

2. In Emma, Mr. Knightley, keen observer of Frank and Jane, conjures up Cowper:

…he could not help remembering what he had seen; nor could he avoid observations which, unless it were like Cowper and his fire at twilight,

‘Myself creating what I saw,’

brought him yet stronger suspicion of there being a something of private liking, of private understanding even, between Frank Churchill and Jane. [Emma, vol. III, ch. 5, quoting The Task, Book IV, “The Winter Evening”].

3. Fanny in Mansfield Park twice quotes Cowper:

Her horror at Mr. Rushworth’s plans to “improve” Sotherton:

Cut down an avenue! What a pity! Does not it make you think of Cowper? ‘Ye fallen avenues, once more I mourn your fate unmerited’ (from The Task, Book I, “The Sofa”)

And later, Fanny, stranded in Portsmouth, again quotes Cowper in Vol. III, ch. 14:

Her eagerness, her impatience, her longings to be with them, were such as to bring a line or two of Cowper’s Tirocinium forever before her. “With what intense desire she wants her home,” was continually on her tongue, as the truest description of a yearning which she could not suppose any school-boy’s bosom to feel more keenly.

Cowper’s “Tirocinium: or, A Review of Schools” (1785, published with The Task) is a poem Cowper wrote addressed to a father who has sent his son away to school; Cowper “recommend[s] private tuition in preference to an education at school.”

But Cowper is much more than a quote here and there in Mansfield Park. Kerri Savage, in her Persuasions On-line essay: “Attending the Interior Self: Fanny’s ‘Task’ in Mansfield Park,” believes that the character of Fanny actually embodies all that Cowper espouses in The Task, and that “ultimately [Cowper’s] Task emphasizes the individual who makes a difference in the world as one who ‘attends to his interior self.’ Cowper contrasts the immorality in the city with the quiet, green rural life that nurtures the introspective moral life,” as we saw above. Sounds just like Fanny, doesn’t it?

************

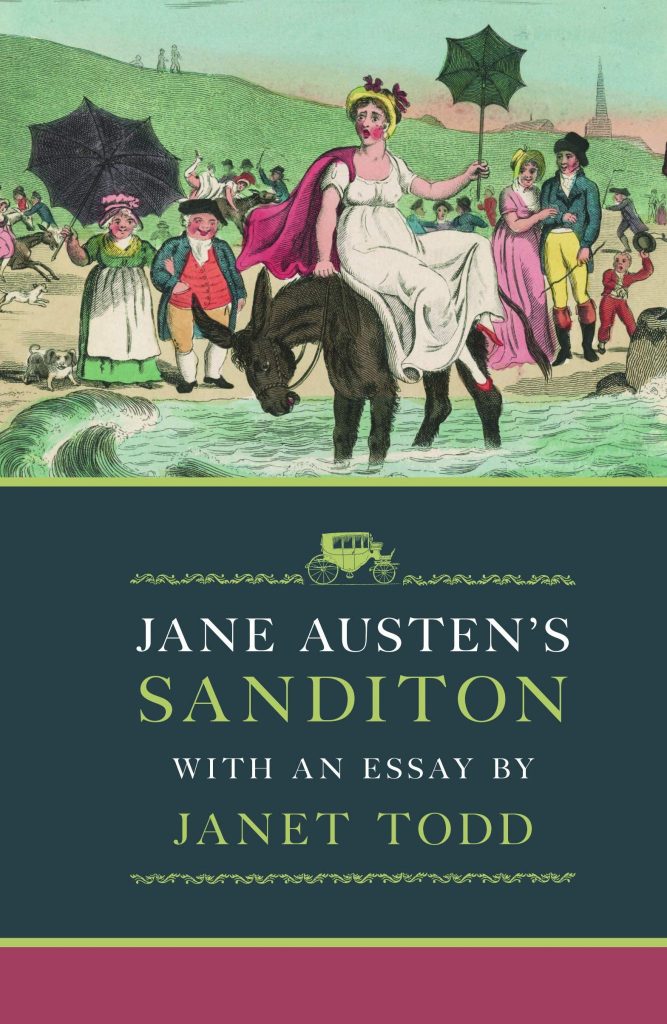

5. And in Austen’s unfinished Sanditon, Cowper is found in Mr. Heywood’s responding to Mr. Parker that he knows not a thing about the famous bathing spot Brinshore:

“Why, in truth, sir, I fancy we may apply to Brinshore, that line of the Poet Cowper in his description of the religious Cottager, as opposed to Voltaire – ‘She, never heard of half a mile from home’” [from “Truth” in Poems, 1782)

….Cowper’s point being that the happy cottager is content with her faith and her rural life, unlike the worldly Voltaire:

Full-text is here: https://www.eighteenthcenturypoetry.org/works/o3794-w0030.shtml

She for her humble sphere by nature fit,

Has little understanding, and no wit,

Receives no praise, but (though her lot be such,

Toilsome and indigent) she renders much;

Just knows, and knows no more, her bible true,

A truth the brilliant Frenchman never knew,

And in that charter reads with sparkling eyes,

Her title to a treasure in the skies.

Oh happy peasant! Oh unhappy bard!

His the mere tinsel, her’s the rich reward;

He prais’d perhaps for ages yet to come,

She never heard of half a mile from home…

*****************

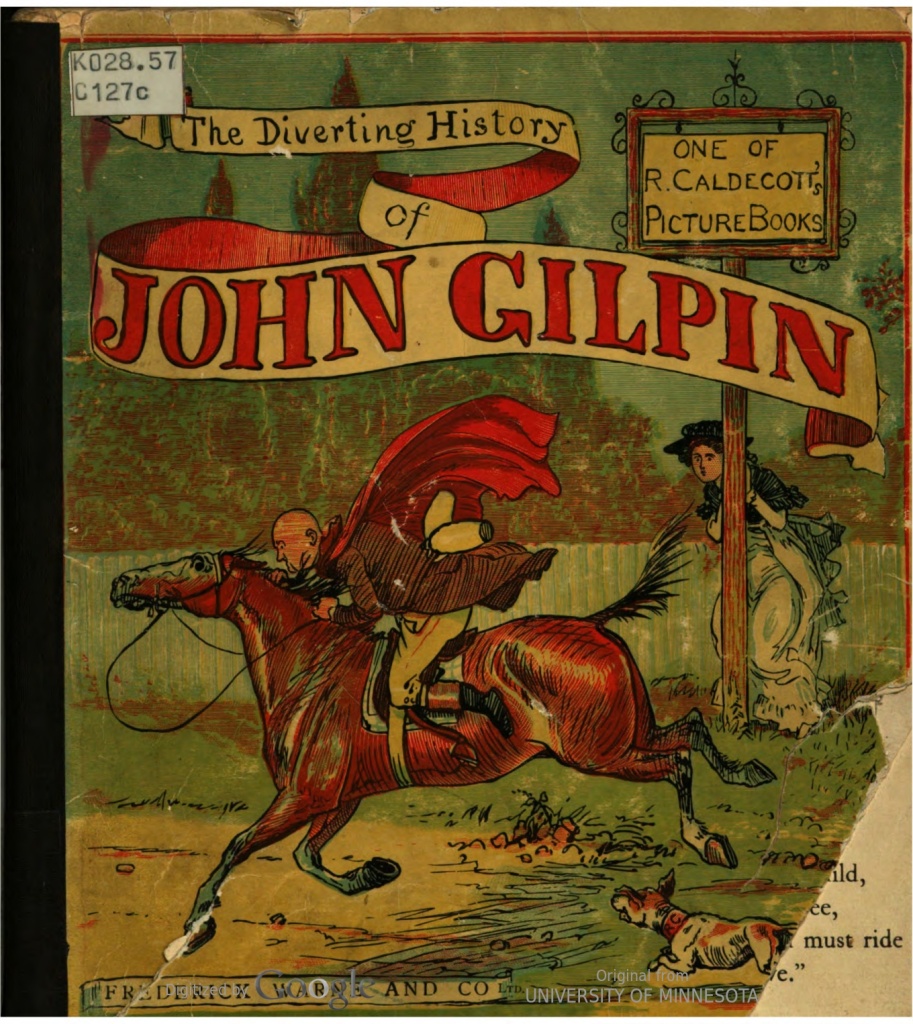

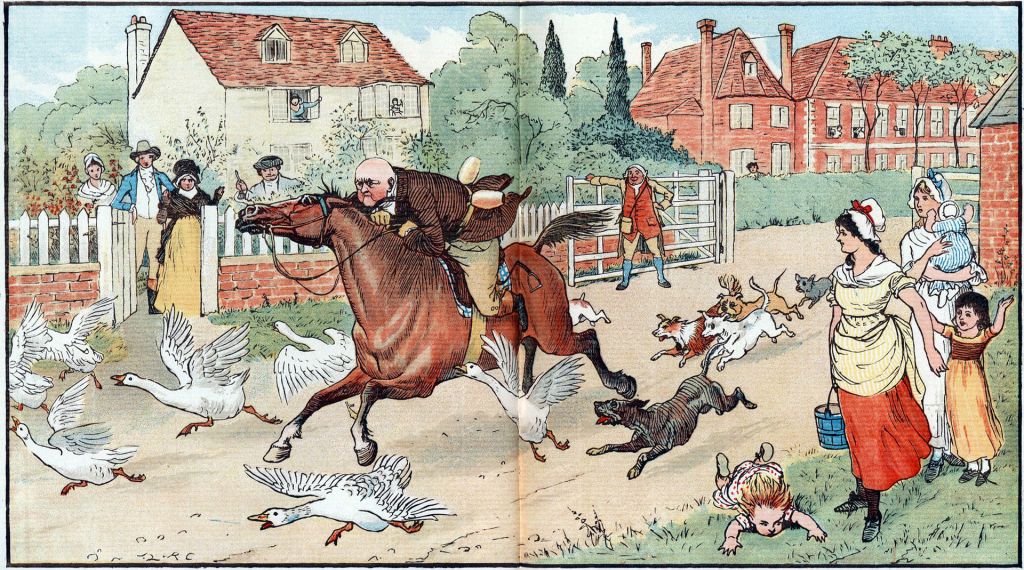

We think of Cowper as a moral, religious poet, with a tendency to melancholy, musing on the beauties of nature and rural life, and why Henry emphasized Austen’s appreciation of him in his overly sanitized biographical essay. But in reading a few poems [can I confess to not doing much with Cowper before? – here’s an Aside: I looked in all my college British Literature texts – Cowper is there, but we touched on nary a single one of his poems!]… but in now finally reading a few of his poems, I do find much humor, especially the very comic “The Diverting History of John Gilpin.”

First published anonymously in The Public Advertiser in 1782, and then in The Task in 1785, “John Gilpin” has been rendered into a number of children’s books, notably by Randolph Caldecott in 1878 – his illustration of Gilpin on his wild run has even become the symbol of the esteemed children’s book award, the Caldecott Medal:

Randolph Caldecott, John Gilpin [wikipedia]

It was also illustrated by Charles E. Brock, noted illustrator of Jane Austen’s novels. [I love these connections!]:

And certainly knowing the backstory of and a reading of the beginning of The Task, can bring to mind an appreciative young Austen reading these works with much laughter and perhaps a bit of idea-plucking for her very own juvenilia?

Here’s “The Sofa” story and how The Task came to be, as Cowper describes it himself:

The history of the following production is briefly this. A lady, fond of blank verse, demanded a poem of that kind from the Author, and gave him the SOFA for a subject. He obeyed; and, having much leisure, connected another subject with it; and, pursuing the train of thought to which his situation and turn of mind led him, brought forth at length, instead of the trifle which he at first intended, a serious affair – a Volume. [Advertisement to The Task, 1785].

The Lady in question was Lady Ann Austen [no relation!], and the interesting history of Lady A and Cowper is a project for another day – but I send you to this essay by K. E. Smith if your curiosity has been roused and you must know the details: https://cowperandnewtonmuseum.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Vol02_2_1.pdf

“The Sofa” begins thus: from The Task, A Poem, In Six Books, Book I. The Sofa.

SING the SOFA. I who lately sang

Truth, Hope and Charity, and touch’d with awe

The solemn chords, and with a trembling hand,

Escap’d with pain from that advent’rous flight,

Now seek repose upon an humbler theme;

The theme though humble, yet august and proud

Th’ occasion — for the Fair commands the song.

We can recall Austen’s penchant for sofas in her juvenilia – one is always quite relieved to find one always at the ready when needed!

[Note: Laurie Kaplan in her Persuasions On-Line essay references other aspects of Austen’s juvenilia in relation to Cowper’s love of the Country vs. the City:

“…for example, in “Letter the 4th: Laura to Marianne” in Love and Freindship, Jane Austen may have been alluding laughingly to Cowper’s preference for the simple life. Laura tells Marianne that she has been warned: “‘Beware of the insipid Vanities and idle Dissipations of the Metropolis of England; Beware of the unmeaning Luxuries of Bath & of the Stinking fish of Southampton’” (78-79). “‘Alas!,’” Laura exclaims, “‘What probability is there of my ever tasting the Dissipations of London, the Luxuries of Bath or the stinking Fish of Southampton? I who am doomed to waste my Days of Youth & Beauty in an humble Cottage in the Vale of Uske.’”]

A Short History of William Cowper.

You can read all you need to know about William Cowper at the excellent Cowper & Newton Museum website: , as well as at The Poetry Foundation.

I offer you a brief version: [short-shift really – do yourself a favor and read all the links I provide – it is all very interesting, whether my English professors at the time thought so or not…]

William Cowper (1731-1800) was born in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire, and was known for his nature, religious, and humanitarian poetry. He was the most-read poet between the eras of Alexander Pope and William Wordsworth. Coleridge called him “the best modern poet,” and he is considered a major influence on the Romantic poets.

[A totally irrelevant Aside: I lived for a number of years in Barkhamsted, Connecticut, which was incorporated in 1779 and named after England’s Berkhamsted. The Town of Barkhamsted presented Berkhamsted with a gavel and block on July 4, 1976 in celebration of the United States Bicentennial – the Berkhamsted Town Council uses it in its meetings. I wonder if I had known about William Cowper at the time, if I would have been better versed in his poetry today!]

************

Cowper’s friendship with John Newton [hence the combined Museum in their names] was foundational in many ways in Cowper’s life and writings. Newton was a former captain of a slave ship who became a staunch abolitionist, wrote the hymn “Amazing Grace,” and invited Cowper to contribute hymns to his Olney Hymns (1779) – Cowper wrote 67 of them [some sources say 68]! Newton also wrote the preface to Cowper’s first published Poems (1782) – this was suppressed by the publisher who thought its overly religious tone might discourage readers, but the preface is here in this 1st edition Godmersham copy, making it the earliest of printing runs before Johnson stepped in and had it removed, and the more rare indeed.

You can read that 8-page Preface here in the 1794 6th ed: https://www.wmcarey.edu/carey/cowper/newton-preface.pdf

In a letter of 3 October 1790, Cowper wrote to Joseph Johnson, asking him to reinstate the preface—which was done for the 5th edition of 1793 and for all subsequent editions published by Johnson, including the 6th of 1794. [I thank Peter Sabor for this information. located in The Letters and Prose Writings of William Cowper. 5 vols. Oxford UP, 1979-86].

Newton’s Thoughts upon the African Slave Trade (1788) influenced Cowper in his “The Negro’s Complaint,” a poem often quoted, even by Martin Luther King, Jr. You can read that here as well.

It was meant to be sung as the ballad “Admiral Hosier’s Ghost” to the tune of “Come and Listen to my Ditty” – you can listen to the first stanza here, with thanks to the Smithsonian Folkways Recordings:

The Negro’s Complaint

[first stanza]

Forc’d from home and all its pleasures,

Afric’s coast I left forlorn;

To increase a stranger’s treasures,

O’er the raging billows borne.

Men from England bought and sold me,

Paid my price in paltry gold;

But, though theirs they have enroll’d me,

Minds are never to be sold….

************

Cowper’s life was a roller-coaster of manic episodes, poetry his main outlet for expression. He was trained in the Law but did not practice [hence his “of the Inner Temple, Esq.”], and seemed to have been dependent on the kindness of friends and loved ones to get him through his trying times. He published his first book of Poems in 1782, not a success apparently; published his “Epitaph on a Hare” [see above for Austen’s reference to the “Tame Hares”!] in The Gentleman’s Magazine in 1784 (as well as Cowper’s letter on his hares which you can read here: https://www.cowperandnewtonmuseum.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/02/mw_tame_hares.pdf, but it was the1785 publication of The Task that did very well and ensured his popularity. He also translated Homer’s Iliad and the Odyssey from the Greek in 1791.

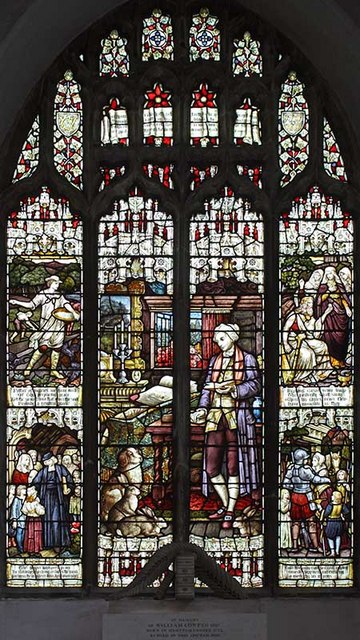

So much of his output was autobiographical, and his 1799 poem “The Castaway” gives the reader a true sense of his emotional struggles. He died in 1800 and is buried at the St. Nicholas Church in East Dereham, where a stained glass window commemorates his life. There is also one at St. George’s chapel in Westminster Abbey, a two light stained glass window in memory of both Cowper and George Herbert.

And he lives on and on because Jane Austen mentions him numerous times in her letters and novels [do they read him now in British Literature college classes I wonder?!]

So Welcome Home Mr. Cowper – we are most pleased you are no longer missing, no longer a LOST SHEEP! Kudos to the Friends of the National Libraries and to the dedication and generosity of the GLOSS team!

************

References:

Austen, Jane. The Letters of Jane Austen. Ed. Deirdre Le Faye. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2011.

Austen, Jane. The Novels: I referred to the Oxford Classics editions, the Chapman Oxford editions, and the Cambridge editions for text and notes.

Cowper and Newton Museum, Olney, UK. Website. https://cowperandnewtonmuseum.org.uk/

Dow, Gillian, and Katie Halsey. “Jane Austen’s Reading: The Chawton Years.” Persuasions On-Line 30.2 (2010). Web. http://www.jasna.org/persuasions/on-line/vol30no2/dow-halsey.html

Kaplan, Laurie. “Sir Walter Elliot’s Looking-Glass, Mary Musgrove’s Sofa, and Anne Elliot’s Chair: Exteriority/Interiority, Intimacy/Society.” Persuasions On-Line 25.1 (2004). Web. http://www.jasna.org/persuasions/on-line/vol25no1/kaplan.html

Savage, Kerrie. “Attending the Interior Self: Fanny’s ‘Task’ in Mansfield Park.” Persuasions On-Line 27.1 (2006). http://jasna.org/persuasions/on-line/vol27no1/savage.htm

Smith, K. E. “‘Many a Trembling Chord’: Lady Austen as Muse.” Web. https://cowperandnewtonmuseum.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/Vol02_2_1.pdf