It is always (to me!) an interesting story how a Lost Sheep gets found – or at least any book detective out there would so describe the thrill of locating a book considered lost to eternity in some auction sale or a the stacks of a library or in someone’s private collection. And such discoveries are often serendipitous – the right place, the right time, or a click of a keyboard and Oh Wow! Look at this!

One of our most exciting finds happened in such a way recently. Though I continue to search library catalogues of colleges and universities and institutions, knowing full well that the provenance of a Knight bookplate might not even be recorded, it is always sheer luck to stumble on one when doing something else entirely…so here’s the story:

One of my book groups was reading Hamnet, by Maggie O’Farrell (fabulous book if you have not read it…), and I was doing some research on the fact vs. fiction questions the book raises. And internet surfing brought me to various Shakespeare-related sites – the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust a treasure trove of information and many images. My Reading with Austen hat is always on and realized I had never searched their library for the Knight bookplates (I search for Chawton, Godmersham, Montagu, Edward, Knight, etc. – and find often that Montagu is misspelled, or he is referred to as “Montagu George, Knight of Chawton,” etc. – these provenance errors complicate searching!) – and the miracle of online catalogue searching brought up a book in their collection with the MGK bookplate! A check in the Reading with Austen catalogue shows this exact title as listed in the 1818 Godmersham catalogue [the images from the SBT have just been added to the listing]: a book by Philip Miller titled The Gardeners Kalendar (1732).

[Here is the link to the SBT catalogue. ]

Eureka! Problem at the time was the SBT was closed, so I waited until they opened to request images – they were as excited as we were to find this Lost Sheep on their very own shelves. There is something comforting about a Jane Austen-related book finding itself at Shakespeare’s birthplace – even Jane (Shakespeare fan that she was) might appreciate this turn of events. We cannot have it back at Chawton House, but this is certainly the next best thing…a Lost Sheep found, and surrounded in Shakespeare no less!

We appreciate very much the Library staff at the SBT copying all the images we need for the website. Here are the details with some information about the book and the author. Can we imagine Austen consulting this very Kalendar at various times during her gardening year?

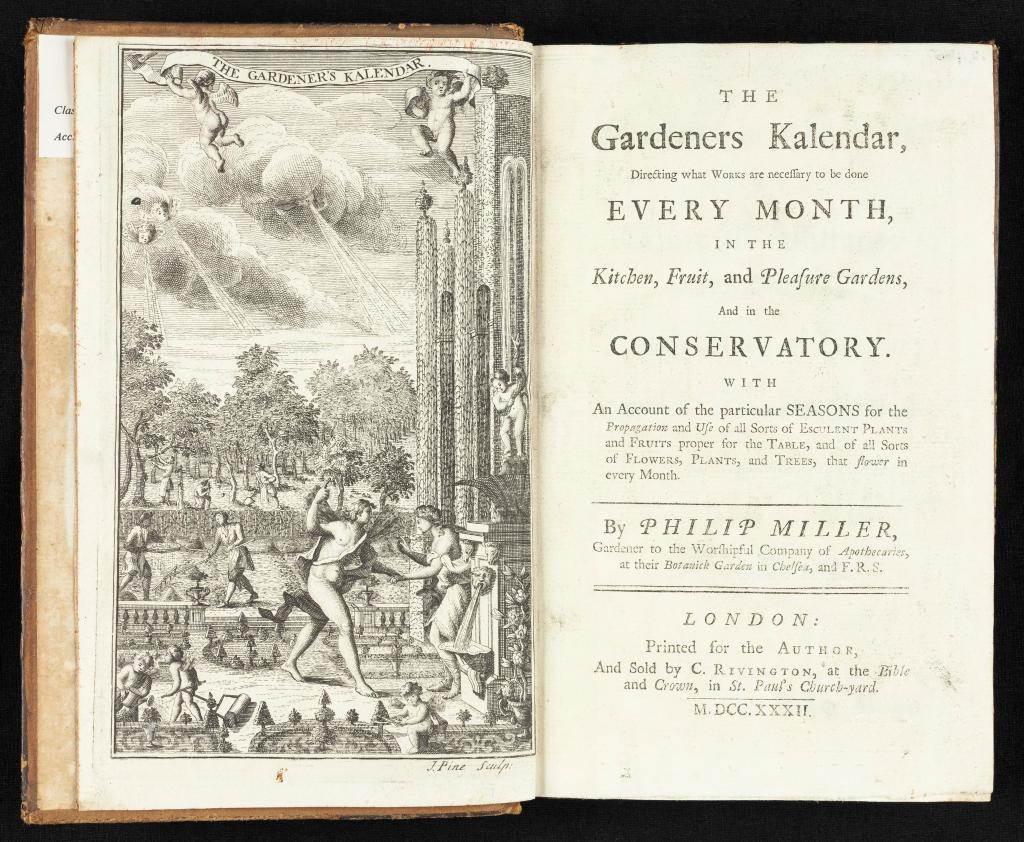

Philip Miller. The gardeners kalendar, directing what works are necessary to be done every month, in the kitchen, fruit, and pleasure gardens, and in the conservatory. With An Account of the particular seasons for the Propagation and Use of all Sorts of Esculent Plants and Fruits proper for the Table, and of all Sorts of Flowers, Plants, and Trees, that flower in every Month. By Philip Miller, Gardener to the Worshipful Company of Apothecaries, at their Botanick Garden in Chelsea, and F. R. S.

London: printed for the author, and sold by C. Rivington, at the Bible and Crown, in St. Paul’s Church-Yard, M.DCC.XXXII. [1732]

xv,[1],252,[4]p.,plate ; 8⁰.

With two final leaves of advertisements.

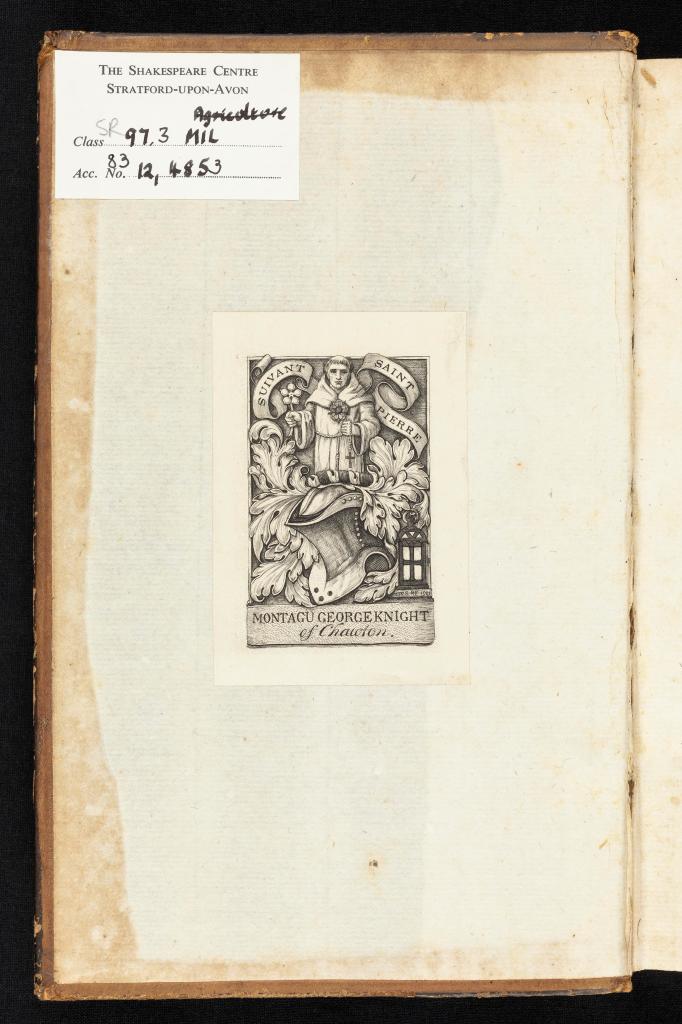

Montagu George Knight, 1844-1914, former owner.

Knight’s bookplate pasted inside front of book.

This book has the least common of the MGK bookplates:

********************************

Philip Miller (1691-1771) was the most well-known of the horticultural writers of the eighteenth-century. He began in London as a florist, grower of ornamental shrubs, and garden designer. It was all the doing of Sir Hans Sloane, who became landlord of the land in Chelsea in 1712 that had been leased to the Society of Apothecaries for their physic garden. In 1722 Sloane transferred it permanently to the Society and recommended that Miller be appointed head gardener – he held this position until shortly before his death in 1771. The Chelsea Physic Garden developed under Miller’s hand into the most richly stocked of any mid-18th century garden, his work there the basis of Miller’s several gardening publications. [You can read about its history here: https://www.chelseaphysicgarden.co.uk/about/history/ ]. It was “largely through [Miller’s] skill as a grower and propagator and his extensive correspondence, the Chelsea botanic garden belonging to the Society of Apothecaries of London became famous throughout Europe and the North American colonies for its wealth of plants, which was continuously enriched by new introductions, notably from the West Indies, Mexico, eastern North America, and Europe.”1

Miller is most known for his The Gardener’s and Florists Dictionary or a Complete System of Horticulture (1724) and The Gardener’s Dictionary containing the Methods of Cultivating and Improving the Kitchen Fruit and Flower Garden, which first appeared in 1731 in a folio and went through eight revised editions in his lifetime. There is much information on Miller’s use of the classifications of Joseph Pitton de Tournefort and John Ray, rather than those of Carl Linnaeus – but he later embraced the Linnaeus nomenclature in his Dictionary of 1768. But I shall avoid this discussion and send you to the resources below if you have any interest in botanical history and the naming of plants.

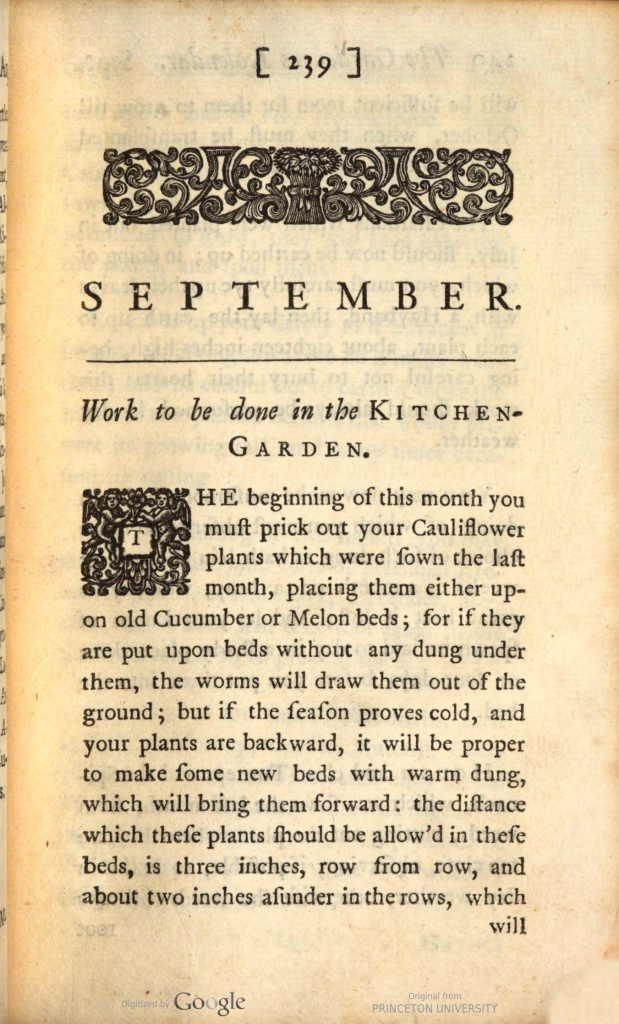

Since this is September, here’s a page sample for what you should be doing in your Kitchen Garden [this is from the 1737 4th ed. at HathiTrust] – it’s all about your cauliflower – there are succeeding entries for work to be done in the Fruit Garden, the Flower Garden, the Pleasure Garden, and the Greenhouse and Stove. You shall be very busy!

You can see the complete text of The Gardeners Kalendar here:

the 1732 1st edition at Google Books: https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Gardiners_Kalendar_Directing_what_Wo/O5xgAAAAcAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

and the 1737 4th edition at HathiTrust:

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=njp.32101037690227&view=1up&seq=11

*********************

One interesting bit is that it was Philip Miller who sent the first long-strand cotton seeds, which he had developed, to the new British colony of Georgia in 1733. They were first planted on Sea Island, off the coast of Georgia, and hence derived the name of the finest cotton, Sea Island Cotton. [There is inconsistent information on this – you can read the Stephens article cited below for a full account.] But this adds to the whole picture of Miller’s hand in propagation not only in England but also in the colonies – and we all know that cultivation of cotton sustained one part of the Triangular Trade and perpetuated the slave trade and system of slavery in order to produce and transport to England as much of this cotton product as possible. This too is another story – but all things connect as anyone trying to research the simplest thing knows – a Godmersham book found at the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, written by a man who had a hand in the development of cotton in the colonies which sustained the slave trade, which then of course leads us to Mansfield Park…and really what was Jane Austen’s “dead silence” all about…

What a digression!

********************

Though Miller’s most well-known books (noted above), available in many editions through the years, are not listed in the 1818 catalogue, there is one other Philip Miller book in the Godmersham collection, also in the 1908 Chawton library, and this is still a Lost Sheep:

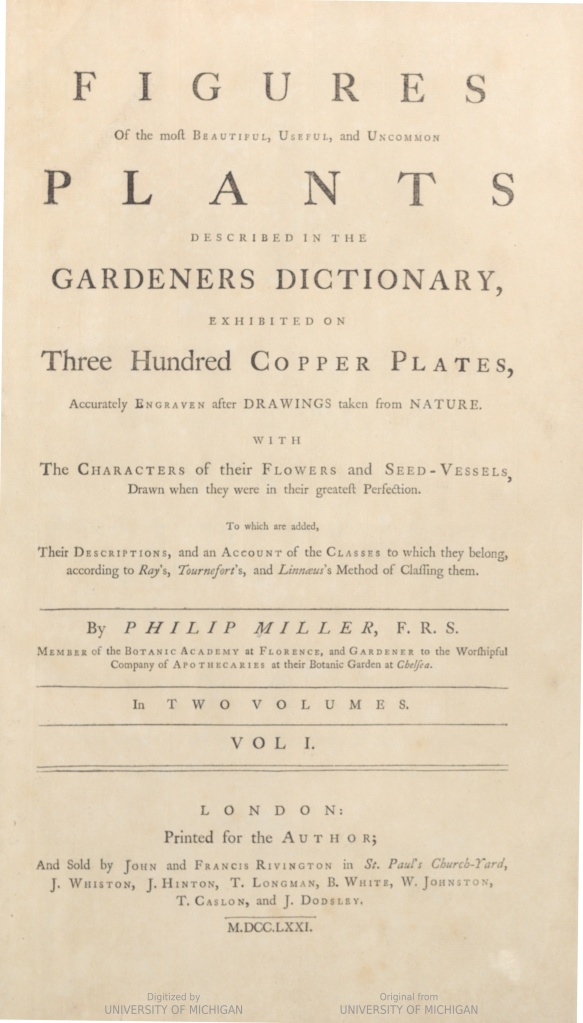

Figures Of the most Beautiful, Useful, and Uncommon Plants described in The Gardeners Dictionary, exhibited on Three Hundred Copper Plates, Accurately Engraven after Drawings taken from Nature. With The Characters of their Flowers and Seed-Vessels, Drawn when they were in their greatest Perfection. To which are added, Their Descriptions, and an Account of the Classes to which they belong, according to Ray’s, Tournefort’s, and Linnæus’s Method of Classing them. By Philip Miller, F.R.S. Member of the Botanic Academy at Florence, and Gardener to the Worshipful Company of Apothecaries at their Botanic Garden at Chelsea. In Two Volumes.

London: Printed for the Author; And Sold by John Rivington in St. Paul’s Church-Yard, A. Millar, H. Woodfall, J. Whiston and B. White, J. Hinton, G. Hawkins, R. Baldwin, J. Richardson, W. Johnston, S. Crowder, P. Davey and B. Law, T. Caslon, and R. and J. Dodsley, 1760.

According to a Sotheby’s sale catalogue, the 300 plates of various plants were drawn by Richard Lancake and two of the leading botanical artists and engravers of the period, Georg Dionysius Ehret and Johann Sebastian Miller (formerly Müller). The work was published by subscription in 50 monthly parts, with each part containing 6 plates, between 25 March 1755 and 30 June 1760. Two later editions were published in 1771 and 1809. It sold in 2017 for £12,500 and there are several currently online listed from $14,000 to $37,000 – but alas and sigh, none of them mention an MGK bookplate, and we can expect if this copy ever does show up, it will be far beyond our pocketbook.

You can see a full text (1771 ed.) of this gorgeous book here: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015063465242&view=1up&seq=5&skin=2021

*****************************

And again, our hearty thanks to the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust for 1.) having this book on their shelves; and 2.) their generosity in providing the images for the website. One more Lost Sheep found is a very comforting thing, and I suppose we have Maggie O’Farrell and her Hamnet to thank for this whole book detective episode!

Resources:

1. See “Miller, Philip” in the Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography.

Other resources on Miller:

Hazel Le Rougetel, “Gardener Extraordinary; Philip Miller of Chelsea, 1691–1771.” Journal of the Royal Horticultural Society 96 (1971): 556–63.

_____. The Chelsea Gardener, Phililp Miller 1691-1771. London: Natural History Museum, 1990.

W. T. Steam, “Philip Miller and the Plants from the Chelsea Physic Garden Presented to the Royal Society of London, 1723–1796.” Botanical Society of Edinburgh Transactions 41 (1972): 293–307.

S. G. Stephens. “The Origin of Sea Island Cotton.” Agricultural History 50.2 (1976): 391-99.