This is a continuation of recording the diaries of Charles Bridges Knight, son of Edward Knight, and his mentions of the books he is reading in the Godmersham Park Library. We thank Austen scholar Hazel Jones for so graciously sharing her finds with us. It very much brings this library to life as we imagine Charles sitting and reading there, much like his aunt Jane Austen would have done several years before. Some of his diary entries are about the Library itself – fires and warmth (or lack thereof), pictures, outside trees, etc., which brings us vividly back to Austen’s own comments of being there: “Mistress of all I survey…”

This is a continuation of recording the diaries of Charles Bridges Knight, son of Edward Knight, and his mentions of the books he is reading in the Godmersham Park Library. We thank Austen scholar Hazel Jones for so graciously sharing her finds with us. It very much brings this library to life as we imagine Charles sitting and reading there, much like his aunt Jane Austen would have done several years before. Some of his diary entries are about the Library itself – fires and warmth (or lack thereof), pictures, outside trees, etc., which brings us vividly back to Austen’s own comments of being there: “Mistress of all I survey…”

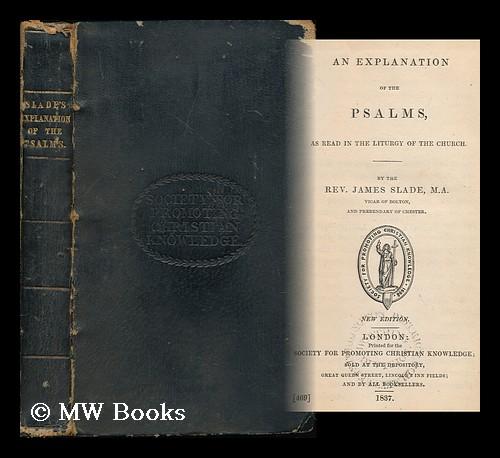

You will see that the majority of books he is reading are religious tracts, commentaries, sermons, and such (all but one are by old white men as you will see – I cannot resist the comment…) – Charles was ordained in 1828 and was the curate of West Worldham and later rector of Chawton. One might want to whisper the words of Anne Elliot into his ear (in reverse of her advice to Capt. Benwick): perhaps a little more poetry and literature and a little less didactic prose might be added to his reading diet – it may have also enlivened his sermons!

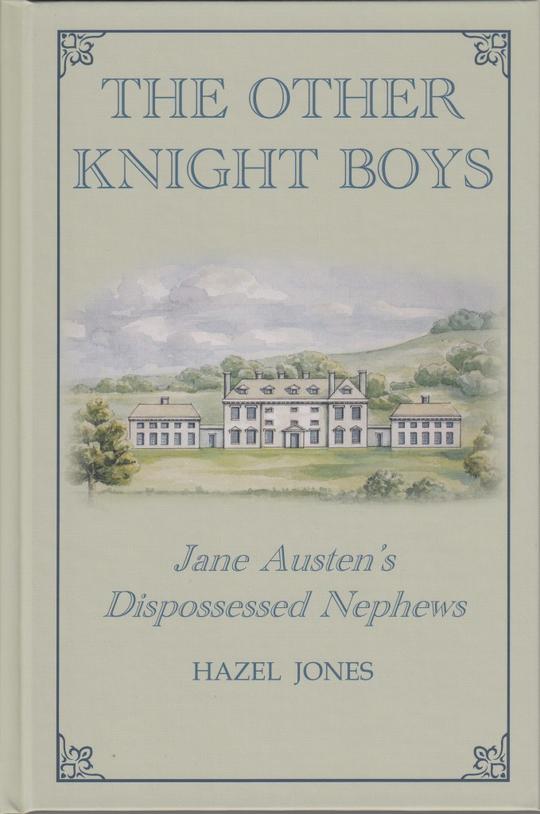

[I will add this so we do not too hastily align Charles with the idea he is a real-life Mr. Collins, picturing him quoting from Fordyce at every opportunity when in the company of young Ladies. Hazel tells me that Charles was, at the time of these diaries, doing clerical duties at the parish in Molash, a small village in Kent near Godmersham – he was busy at work preparing sermons and offering solace to parishioners, and he often stood in for the Revd. Richard Tylden at Chilham. As we can see from his reading material over these few years, he was certainly diligent in his duties. We will have to wait for Hazel’s book on all of Jane Austen’s nephews to be published (hopefully later this year) for more details – we shall find I think that Charles has a more interesting story than just these lists of religious and philosophical books!]

You can read the previous blog posts here:

A quick review of Charles: Charles Bridges was born March 11, 1803 at Godmersham  Park in Kent, the 8th child of Jane Austen’s brother Edward Knight and Elizabeth Bridges. He was a commoner at Winchester* from 1816-1820, attended Trinity College, Cambridge and was ordained in 1828. He was the curate of West Worldham in Hampshire and rector of Chawton from 1837-1867. He died unmarried on October 13, 1867, aged 64 years. He is buried in the graveyard at the St. Nicholas Churchyard in Chawton (Section B: Row 2. 70 ).

Park in Kent, the 8th child of Jane Austen’s brother Edward Knight and Elizabeth Bridges. He was a commoner at Winchester* from 1816-1820, attended Trinity College, Cambridge and was ordained in 1828. He was the curate of West Worldham in Hampshire and rector of Chawton from 1837-1867. He died unmarried on October 13, 1867, aged 64 years. He is buried in the graveyard at the St. Nicholas Churchyard in Chawton (Section B: Row 2. 70 ).

*****

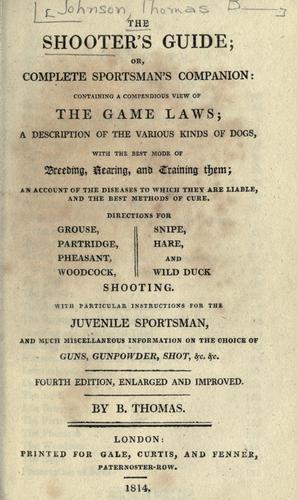

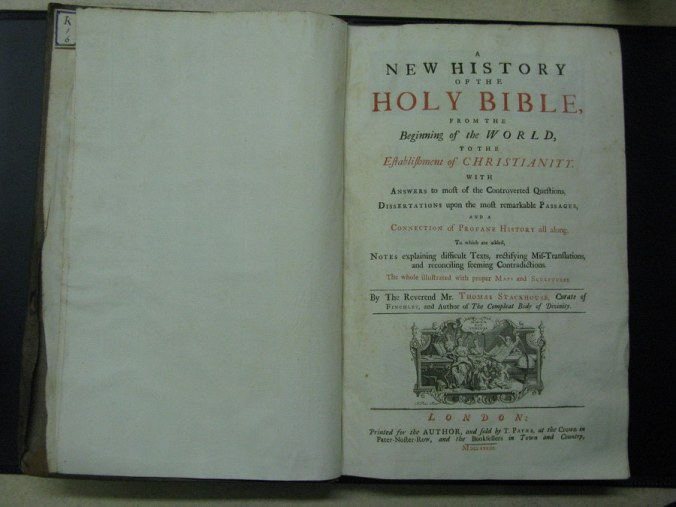

Listed here are the books in the GPL library that Charles mentions, beginning with his Diary no. 5, dated January 1, 1833 – April 30, 1833. Not all these books were in the 1818 catalogue, often being published after that date – please note where the books are in the 1818 catalogue and are Lost Sheep – we are constantly on the alert for these!

‘January 1 (1833) … not going out much on account of the gout I have plenty of time to read all day. I read in the library until luncheon time, then take a ride, then read in my room till dinner …’

‘Thursday Feby 28 … Rice & I played at Rackets in the Library.’

Ok, now what is “Rackets” being played in the Library?? Defined on Wikipedia as follows:

Rackets court – Eglinton Castle

“Rackets or racquets is an indoor racket sport played in the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland, United States, and Canada. Historians generally assert that rackets began as an 18th-century pastime in London’s King’s Bench and Fleet debtors prisons. The prisoners modified the game of fives by using tennis rackets to speed up the action. They played against the prison wall, sometimes at a corner to add a sidewall to the game. Rackets then became popular outside the prison, played in alleys behind pubs. It spread to schools, first using school walls, and later with proper four-wall courts being specially constructed for the game. And later, specific indoor courts were built as shown here at Eglinton Castle in 1842.”

The idea of Charles playing against the walls of the library is a tad disconcerting! Would his father approve? Would Jane??

In Diary no. 6 (May – Nov 1833), Hazel tells us: “No mention of books or the library. Mainly hunting and fishing and generally slaughtering anything that moves.”

In Diary no. 8 (Oct 1834 – Oct 1835), we find Charles back at work on his reading:

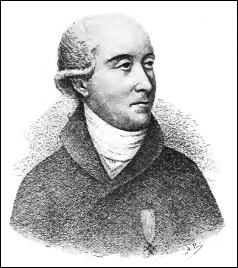

‘Sunday March 8 … Read some of Hannah More’s correspondence;’ and again on ‘Monday March 9 … I read some of Hannah More’

Hannah More by Henry William Pickersgill, 1821

In the 1818 catalogue, there are three Hannah More (1745-1833) titles:

– Strictures on the modern system of female education. With a view of the principles and conduct prevalent among women of rank and fortune. 9th ed. By Hannah More. In two volumes. London: Printed for T. Cadell Jun. and W. Davies, in the Strand, 1799. A Lost Sheep!

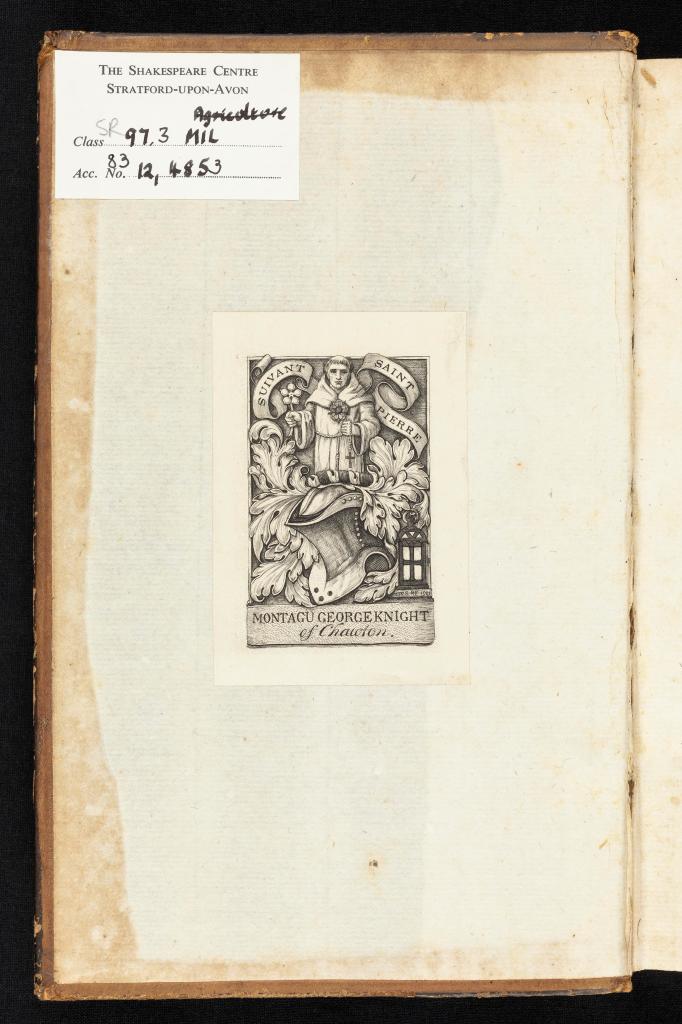

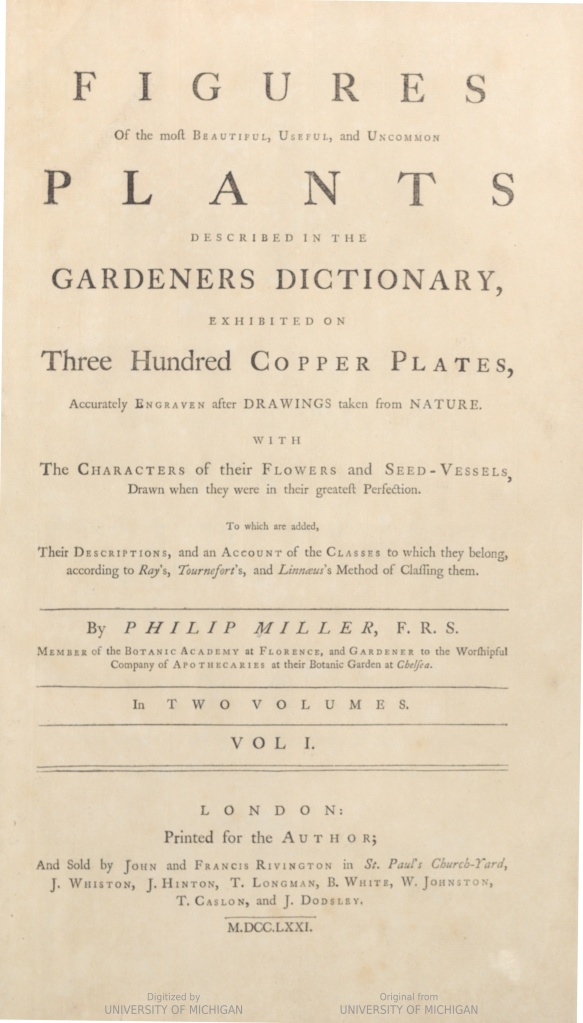

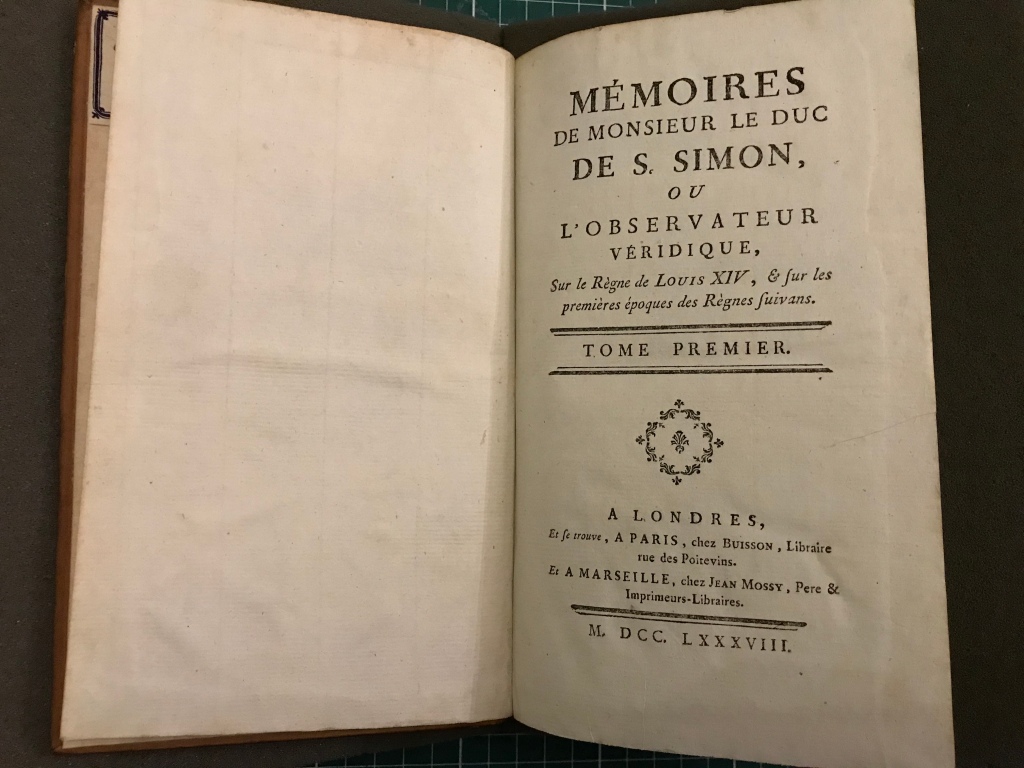

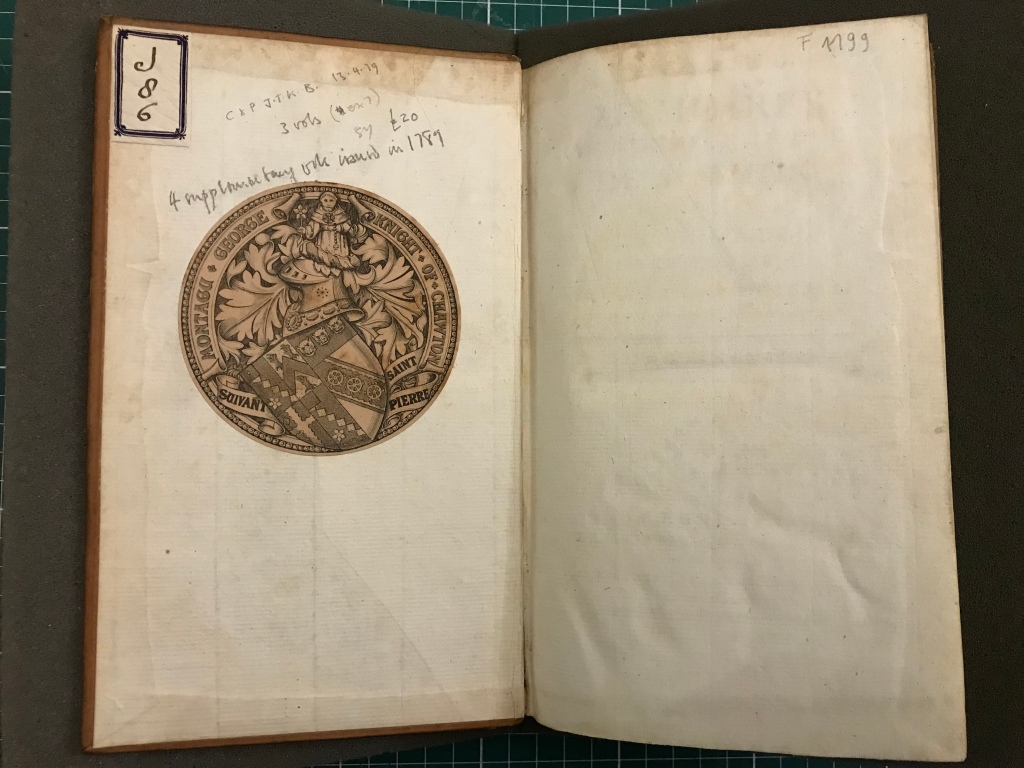

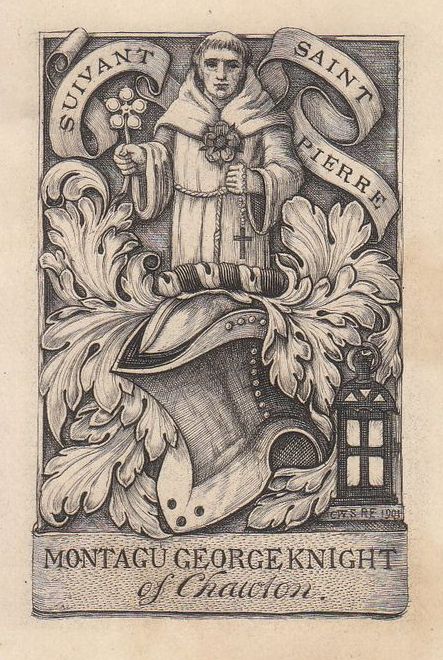

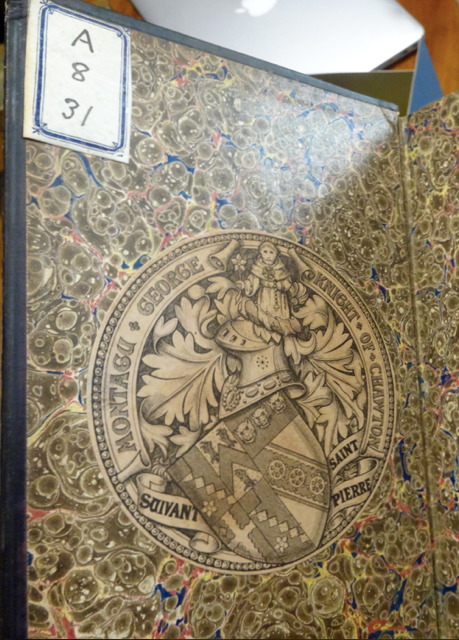

– Coelebs in search of a wife. Comprehending Observations on domestic habits and manners, religion and morals. The ninth edition. In two volumes. London: Printed for T. Cadell & W. Davies, in the Strand, 1809. In the Knight Collection, with the less common oblong Montagu George Knight bookplate:

– Florio: A Tale, For Fine Gentlemen and Fine Ladies: and, The Bas Bleu; or, Conversation: Two Poems. 1st ed. London: Printed for T. Cadell, in the Strand, 1786. A Lost Sheep!

Hannah More (1745 – 1833) was an English religious writer and philanthropist, a poet and a playwright, and an original member of the BlueStockings. She became more and more evangelical in her writings and campaigned actively against the slave trade.

Dr Syntax with a Blue Stocking Beauty – T. Rowlandson

Austen famously writes of More in a few letters to Cassandra:

You have by no means raised my curiosity after Caleb; – my disinclination for it before was affected, but now it is real; I do not like the Evangelicals. – Of course, I shall be delighted when I read it, like other people- but till I do, I dislike it. [Ltr. 66, 1809]

And in her next letter, Austen speaks on being corrected in the spelling of the title with the added Dipthong [sic]: “I am not at all ashamed about the name of the Novel… the knowledge of the truth does the book no service; – the only merit it could have was in the name of Caleb, which has an honest, unpretending sound; but in Coelebs, there is pedantry & affectation. – Is it written only to Classical Scholars?… [Ltr. 67, 1809]

And Austen later refers to More’ new book Practical Piety published in 1811. [Ltr. 74, 1811]

But Charles refers to More’s “correspondence,’ which I find to be first published in 1835: Memoirs of the life and correspondence of Mrs. Hannah More, by William Roberts, so this may have been added to the library just recently after its publication – OR he refers to another book entirely…

Back to Charles:

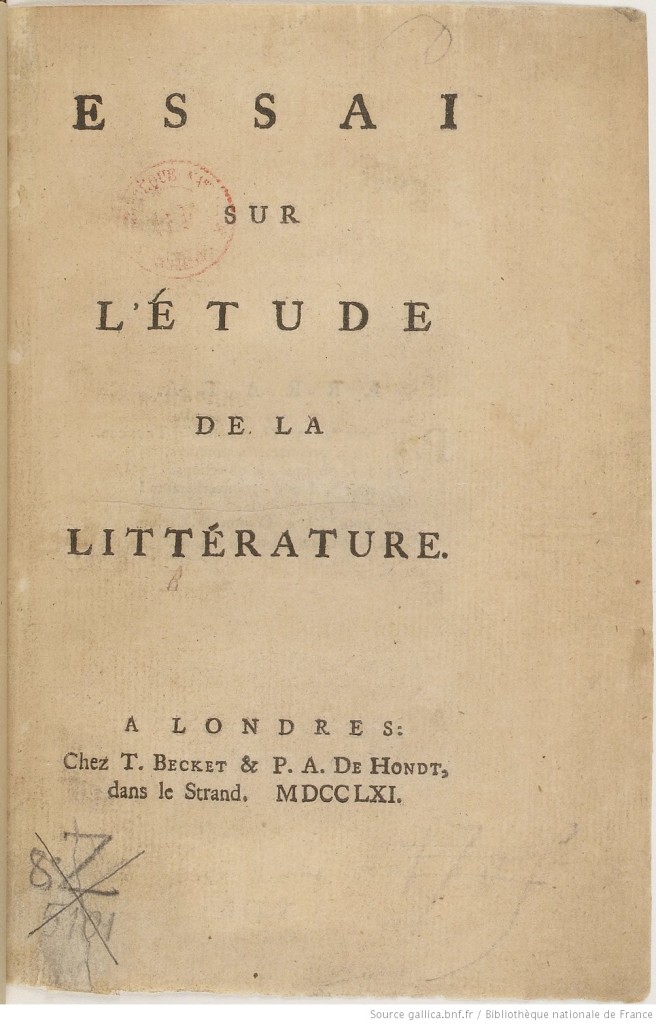

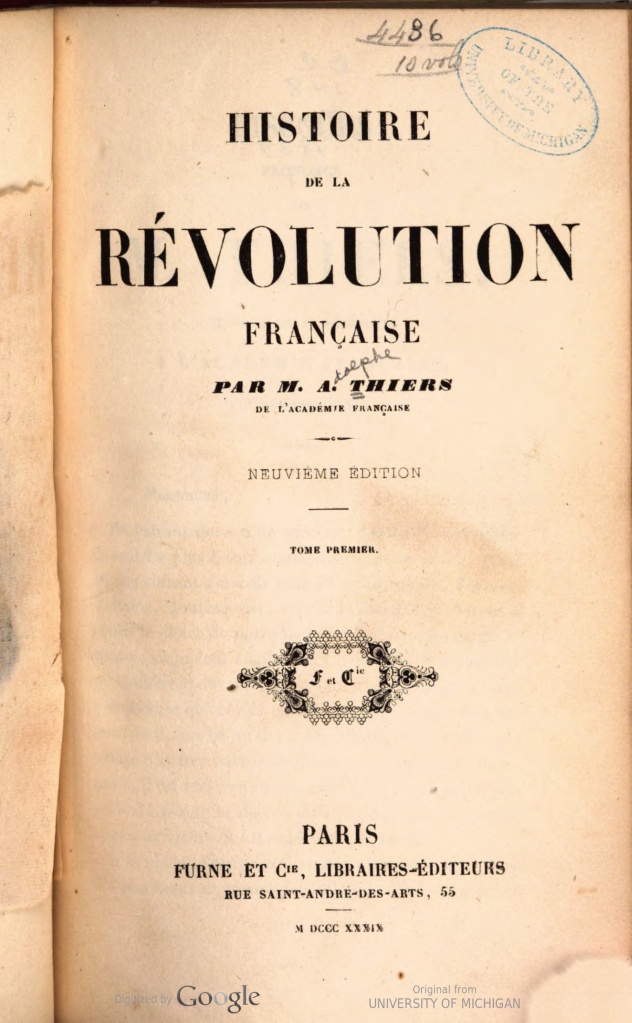

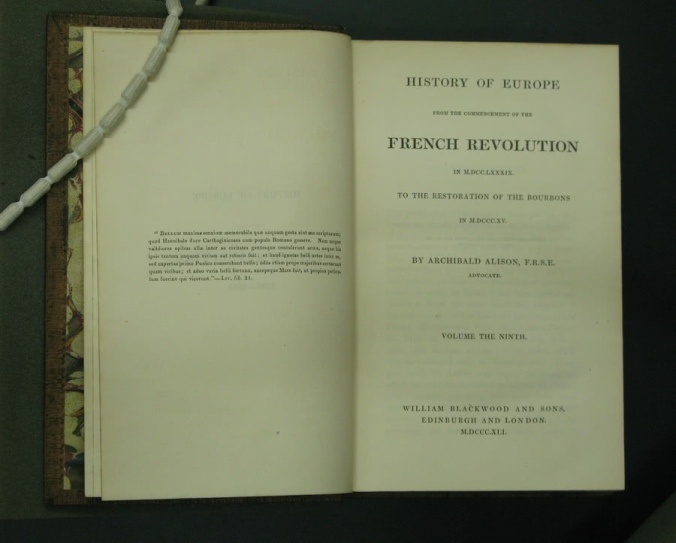

‘September 29 Tuesday … I read a chapter in the old & in the new testament as soon as I am dressed, & then some of Taylors holy living … At 1/2 past 8 I go to Henry & read to him the morning psalms, two chapters out of each testament, & some of Sherlock on Death. After breakfast I write a sermon or read for it, or read Burnets own times till between 11 & 12 … I want to read some French too, but have no time, & also Chillingworth, but have no time. I am also reading at odd times Le Bas s life of Wickliffe.’

‘Wednesday Sepr 30 … Began reading George’s Warsaw tour after dinner.’ (Brother George Thomas Knight)

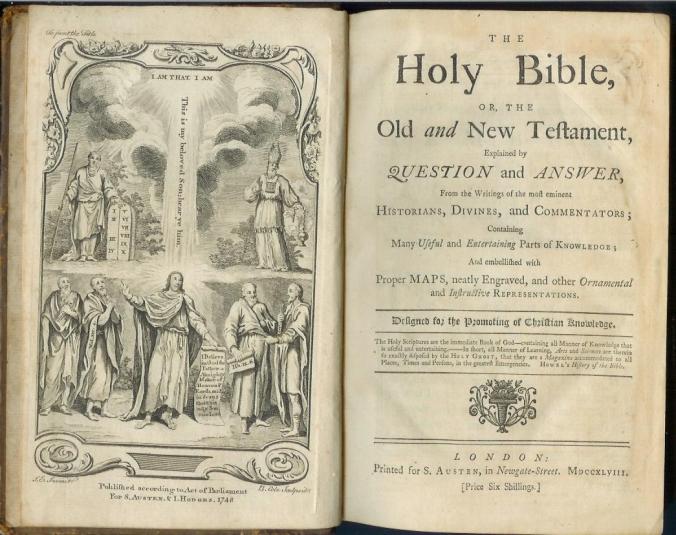

‘Friday Oct 2 … I finished the preface to Bagster’s Bible, & am now going to begin Genesis. It is impossible to look at all the references, & I think it is a good plan to read with some particular object in view.’

So lots here:

– Taylor’s holy living: The only Taylor listed in the catalogue is The Worthy Communicant – but Taylor also published a work titled The Rule and Exercises of Holy Living (1650), not found in the catalogue.

William Sherlock.

– Sherlock on Death:

William Sherlock: The 1818 catalogue lists several works by William Sherlock, including his A Practical Discourse concerning Death, published in London in 1751 (it was a very popular work, originally published in 1689). This is A Lost Sheep!

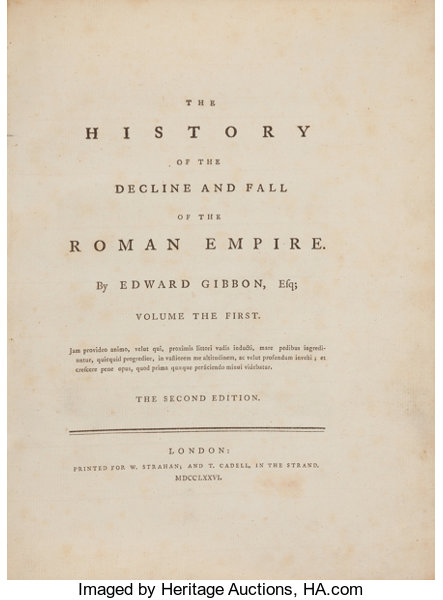

– Burnet’s times must refer to Gilbert Burnet’s Bishop Burnet’s History of His Own Time. Vol. I. From the Restoration of King Charles II. to the Settlement of King William and Queen Mary at the Revolution: To which is prefix’d A Summary Recapitulation of Affairs in Church and State from King James I. to the Restoration in the Year 1660. London, 1724, 1734. Charles mentions reading this a number of times in his diaries – and happily we find this in the Knight Collection, with the older Thomas Knight bookplate:

– Chillingworth refers to Richard Chillingworth, The Religion of Protestants (1674) – see Part I for more information.

John Wycliffe at work

– Le Bas Life of Wickliffe is a book dilemma: Charles Webb Le Bas wrote The Life of Wiclif in 1832, not in the catalogue. William Gilpin wrote The Lives of John Wicliff, and the 1766 edition was in the GPL – and alas! A Lost Sheep! – but not the book Charles was reading….

– Bagster’s Bible: Samuel Bagster published his first Polyglot Bible in 1816; his Comprehensive Bible (see the next entry for Oct 3) was first published around 1829. Neither appears in Edward’s 1818 catalogue.

Diary no. 9 (Oct 3, 1835 – Jan 18, 1836)

Charles has a few comments on Bagster’s Bible:

‘Saturday Oct 3d 1835. I got up at 6. Read the first chapter in Genesis in Bagster’s Comprehensive Bible, referring to all the New Testament references, as I had determined, but found so many of them quite nihil ad rem [nothing to the point], only containing fanciful allusions to the text, that I resolved to give it up, and mean in future only to refer to such as relate to passages I don’t understand, or are of any particular interest.’ [So much for Bagster… ‘nothing to the point’ seems awfully harsh!]

‘Sunday Oct 4th … I finished Sherlock on Death to Henry for the 3d time. I wonder how long we shall go on reading it once a year.’ [goodness, this seems depressing!]

‘Thursday Oct 6th … I looked over an old journal to Naples in 1825 – 6, & mended a little my Kissingen journal – It is the fashion now to read these things, & Marianne & At Louisa have begun by George’s last Schwalbach tour …(family journals) … I read some of Burnets times.’ (Many other refs to the latter, including ‘like them very much’.)

‘Sunday Oct 11th … I wrote a list of chapters to be read by the sick, taken from Stonehouse’.

– Sir James Stonhouse (1716–1795) was an English physician and cleric – he published many treatises on religion, one of them Every Man’s Assistant and the Sick Man’s Friend, 1788 – to which Charles might be referring. It is not in the 1818 catalogue.

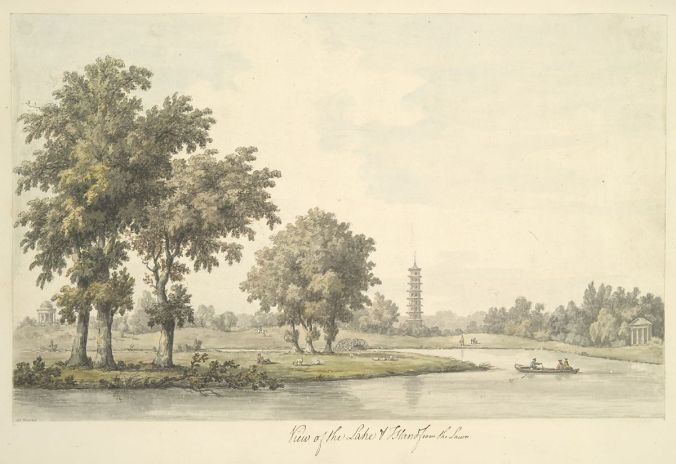

‘Monday Oct 12th … The Sycamore close to the Library was cut down today: I wish a great many more trees were moved; the house is too much shut in by them.’

‘Tuesday Oct 13 … read a good deal of Burnets’ times. What a disgraceful set of libertines the great men of Charles the 2ds time were! Even the churchmen seem to have had but little religion; as for the way of establishing episcopacy in Scotland, it was quite enough to disgust any reasonable man with the very name, & I should think must have left an impression that has not yet worn away. I sat in the hall and read, as I usually do now, the fire being lighted, & find it very comfortable.’

‘Wednesday Oct 14 … After breakfast I read the thoughts of Pascal for some time. I think them hard, & get on very slow, but like them, they are well argued I think.’

– Blaise Pascal: The only Pascal in the GPL is: Les provinciales ou les lettres ecrites par Louis de Montalte a un provincial de ses amis, et aux RR. PP. Jesuites. By Blaise Pascal. Cologne, 1738. A Lost Sheep!

But Charles is more than likely reading Pascal’s Pensées [Thoughts], incomplete at his death in 1662 and published in 1670. This is not in Edward’s catalogue.

Pascal was a renowned mathematician and Catholic theologian. He invented the first calculator, called the Pascaline, this one on exhibit at the Musee des Arts et Metiers, Paris:

[iamge: By Rama, CC BY-SA 3.0 fr, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=53246694%5D

‘Monday Oct 19 … began Benson’s Hulsean lectures 1820 for the 2d time … I saw the pictures hung up again in the library.’

– Christopher Benson, Hulsean lectures for 1820: Twenty discourses preached before the University of Cambridge in the year 1820 – and not in the catalogue.

Alexander the Great

‘Wednesday Oct 21 … I began Pastor William’s s life of Alexander the great for the 2d or 3d time, & probably shall not go on long with it.

– The Rev. John Williams’s The life and actions of Alexander the Great was published in 1829. It was not in the 1818 catalogue, but is in the 1908 catalogue of Chawton House library.

[Image: Andrew Dunn at Wikimedia commons ]

‘Thursday Oct 22 … ‘I consulted Hooker & Prideaux about the way of spending the Sabbath & the Jewish synagogues. I should think Echard’s eccles. history must be a useful book.’

– We mentioned Hooker’s Ecclesiastical Polity in Part I.

There are two works by Humphrey Prideaux in the 1818 catalogue; perhaps this is the one Charles was reading: The Old and New Testament connected in the History of the Jews and Neighbouring Nations (1715–17). It is in the Knight Collection:

– Echard’s eccles. History is clearly this:

Laurence Echard. A General Ecclesiastical History from the Nativity of our Blessed Saviour to The First Establishment of Christianity By Humane Laws, Under the Emperour Constantine the Great. Containing the Space of about 313 Years. With so much of the Jewish and Roman History as is Necessary and Convenient to illustrate the Work. To which is added, A Large Chronological Table of all the Roman and Ecclesiastical Affairs, included in the same Period of TIme. By Laurence Echard, A. M. Prebendary of Lincoln, and Chaplain to the Right Reverend James, Lord Bishop of that Diocese. London, 1702.

Laurence Echard. A General Ecclesiastical History from the Nativity of our Blessed Saviour to The First Establishment of Christianity By Humane Laws, Under the Emperour Constantine the Great. Containing the Space of about 313 Years. With so much of the Jewish and Roman History as is Necessary and Convenient to illustrate the Work. To which is added, A Large Chronological Table of all the Roman and Ecclesiastical Affairs, included in the same Period of TIme. By Laurence Echard, A. M. Prebendary of Lincoln, and Chaplain to the Right Reverend James, Lord Bishop of that Diocese. London, 1702.

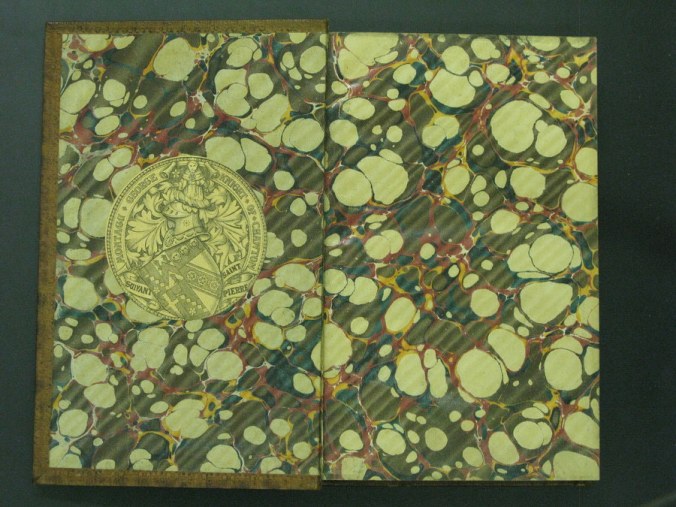

This work is listed in the 1818 catalogue and is in the Knight Collection, with the older  Thomas Knight bookplate and this interesting cover: this Elizabeth Knight is the original cousin with the Knight name which was taken by Thomas Brodnax May in order to inherit the estate in Chawton. It was his son Thomas who adopted Jane Austen’s brother. For a full understanding of all these names see Chawton Manor and Its Owners; A Family History, by William Austen-Leigh and Montagu George Knight.

Thomas Knight bookplate and this interesting cover: this Elizabeth Knight is the original cousin with the Knight name which was taken by Thomas Brodnax May in order to inherit the estate in Chawton. It was his son Thomas who adopted Jane Austen’s brother. For a full understanding of all these names see Chawton Manor and Its Owners; A Family History, by William Austen-Leigh and Montagu George Knight.

There are two other titles by Echard in the catalogue and both are extant in the Knight Collection.

*****

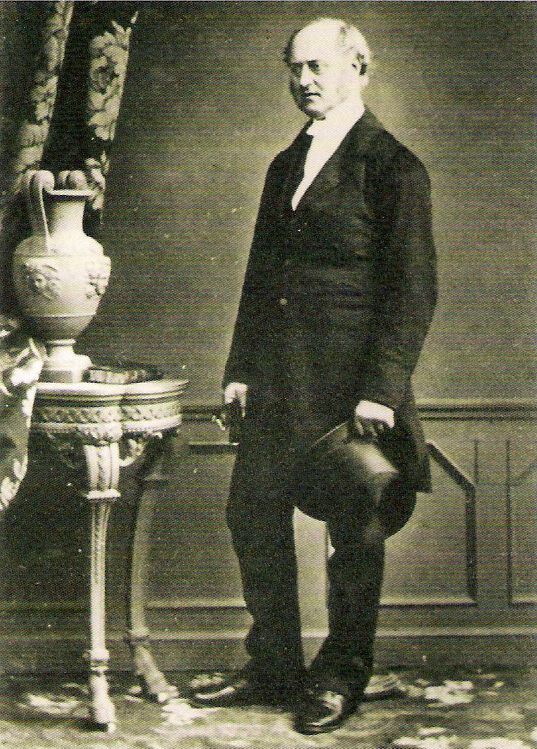

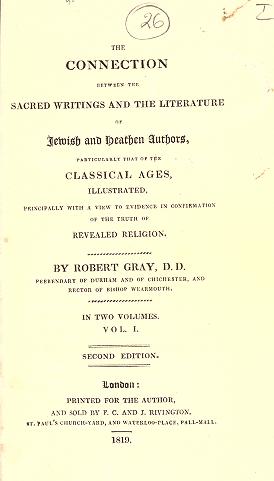

‘Friday Oct 23 … Marked some texts on the Sabbath & looked in Bishop of Bristol’s Ch. history about it.’ – which must refer to:

Robert Gray: The Connection between the Sacred Writings and the Literature of Jewish and Heathen Authors, particularly that of the Classical Ages, Illustrated, principally with a view to evidence in confirmation of the truth of Revealed Religion. By Robert Gray, D. D. Prebendary of Durham and of Chichester, and Rector of Bishop Wearmouth. [Later the Bishop of Bristol], published in London in 1816 – in the 1818 catalogue and A Lost Sheep! You can read the 2nd edition here: https://archive.org/details/connectionsacred01grayuoft/page/n5

Robert Gray: The Connection between the Sacred Writings and the Literature of Jewish and Heathen Authors, particularly that of the Classical Ages, Illustrated, principally with a view to evidence in confirmation of the truth of Revealed Religion. By Robert Gray, D. D. Prebendary of Durham and of Chichester, and Rector of Bishop Wearmouth. [Later the Bishop of Bristol], published in London in 1816 – in the 1818 catalogue and A Lost Sheep! You can read the 2nd edition here: https://archive.org/details/connectionsacred01grayuoft/page/n5

‘Sunday Oct 25th … after dinner dipped into White’s Selborne – but it is impossible to read in a party, & if one goes into one’s own room, it ends always in a nap.’

– Charles is Funny! (who knew!) – he is here talking about Gilbert White’s The natural history and antiquities of Selborne, in the county of Southampton: with engravings, and an appendix. London, 1789 – This 1st edition is in the catalogue and A Lost Sheep!

Gilbert White House

Austen would have been familiar with White, his work and his home – it was not far from her in Steventon and later Chawton. You can visit his house and gardens here. (Gilbert White died in 1793 and left his home to his nephew John White).

[Austen mentions Selborne a few times in her letters – this one dated May 31, 1811 (Ltr. 74 to her sister) speaks of Anna [Lefroy, her niece] going to visit Selborne on the Tuesday: “Poor Anna is also suffering from her cold which is worse today, but as she has no sore throat I hope it may spend itself by Tuesday … She desires her best love to Fanny, & will answer her letter before she leaves Chawton, & engages to send her a particular account of the Selbourn [sic] day.”]

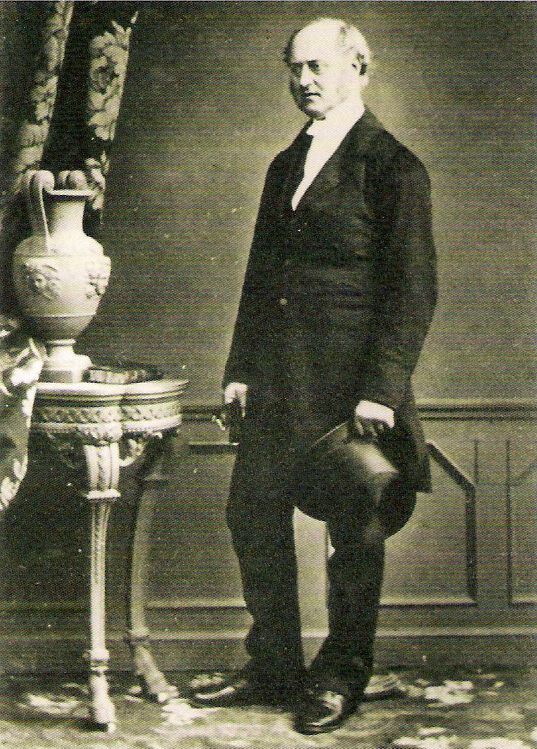

‘Saturday Oct 30th … Read to Henry – a sermon of Porteous.’

– Charles unfortunately doesn’t tell us which sermon, but this is the book: Sermons on Several Subjects. By the Right Reverend Beilby Porteus, D. D. Bishop of Chester. By Porteus, Beilby. London, 1783, 1794 – is in the GPL catalogue and is still in the Knight Collection.

Beilby Porteus (1731 – 1809) was a chaplain to King George III, and the Bishop of Chester and later Bishop of London – he is mostly known for being at the forefront of the abolitionist movement.

‘Sunday Nov 1st … We began the Apocrypha a day or two ago, & read 3 or 4 chapters of the 1st book of Esdras – we have skipped the rest & today began the 2d book.’

Wednesday Nov 4th … I read Blanco White’s Evidence agst catholicism till dinner time.’

– Joseph Blanco White. Practical and Internal Evidence Against Catholicism, With Occasional Strictures on Mr. Butler’s Book of the Roman Catholic Church; In Six Letters. Roman Catholics of Great Britain and Ireland. Joseph Blanco White, 1825 – this is not in the 1818 catalogue.

‘Thursday Nov 5th … read 2 of Horsley’s sermons on the coming of our Saviour.’

‘Saturday Nov 7th … finished Horsley’s sermons on the Sabbath, read one of Sharp‘s on the same subject.’

Samuel Horsley

Charles could be referring to:

– Samuel Horsley. Letters from the Archdeacon of Saint Albans, in reply to Dr. Priestley. With an appendix, containing Short Strictures on Dr. Priestley’s Letters by an unknown Hand. London, 1784. – which is in the 1818 catalogue and remains in the Knight Collection. But Horsley, the Bishop of Rochester, wrote a number of tracts, sermons, and treatises, and Charles may have been reading a different book…

– Sharp? – there is a Samuel Sharp in the catalogue (and in the Knight Collection): Letters from Italy, describing the Customs and Manners of that Country, In the Years 1765, and 1766. To which is Annexed, An Admonition to Gentlemen who pass the Alps, in their Tour through Italy. By Samuel Sharp, Esq. The Third Edition. London, 1767 – but this is unlikely the book with a sermon on the Sabbath…

‘Monday Nov 9th … began Sumner’s sermons on Ctian faith & practice for the 2d time … after dinner I dipped into Pope’s essay on man which is always lying about – it is a very fine piece I think. I am overwhelmed with books just now, that I am reading or want to read – this happens now & then, & on the other hand I am sometimes at a loss what to read. This comes I think of not having a regular course of reading marked out.’ [Note from Hazel: Mr. Knightley needs a word].

– Nothing by Sumner in the 1818 catalogue, but I do find this in searching: A series of sermons on the Christian faith and character, by John Bird Sumner. London, 1823. There are also a number of other Sumner titles extant in the Knight Collection

– Alexander Pope. The Works of Alexander Pope Esq. In Nine Volumes Complete. London, 1751. We can assume this set of nine volumes was what was “always lying about” the GP Library… It is in the catalogue and is extant in the Knight Collection.

‘Wednesday Nov 11th … I read Jebb & Knox before dinner.’

– Jebb and Knox must refer to the Thirty years’ correspondence between John Jebb and Alexander Knox, published in 1834 (compiled by James Forster). Both John Jebb and Alexander Knox were Irish theologians and writers, and mostly known today for this collection of their letters. It is not in the 1818 catalogue.

[Peter Sabor, the creator of the Reading with Austen website, and also a Frances Burney scholar and Director of the Burney Centre at McGill, tells me that Burney had an interesting connection with this very same duo Jebb and Knox: the elderly Mme d’Arblay (Burney) met John Jebb, corresponded with him, and gave him a copy of her Memoirs of Doctor Burney. Jebb appears both in the final volumes of Journals and Letters of Mme d’Arblay, ed. Joyce Hemlow, and in Sabor’s own Additional Journals and Letters of Frances Burney, vol. II, that published last year. I will find these citations and do another post on Burney – she is after all also in the GPL 1818 catalogue – only The Wanderer however, which is interesting in itself – we know that Austen not only read and admired Burney, she also was a subscriber to her Camilla, along with Edward’s adoptive mother Catherine Knight].

[But I digress… see how one thing leads to another?? how in one post there are the seeds for at least 20 more…]

‘Friday Nov 13 … The stove that was in the Billiard room is moved into the library, & was lighted today for the first time: I think it will give more heat than the other did, but is not half enough to warm so large a room with so many outside walls windows & draughts of air.’

[In a letter dated September 23-24, 1813 [Ltr. 89], Austen is visiting Godmersham and she writes Cassandra: “We live in the Library except at Meals & have a fire every Eveng.”]

‘Saturday Nov 14 … read part of Knox’s letter on preaching … I read some of Pope’s essay on Man, & some of a book on the antiquity of the Irish nation, proving that a great grandson of Jephet called Partholan was the first known invader of it …’ [Hazel: This book belongs to Lord George Hill].

The earliest surviving reference to Partholón is in the Historia Brittonum, a 9th-century British-Latin compilation attributed to Nennius. Partholon was the first colonist of Ireland by way of Greece. He is now considered just a character in medieval Irish Christian pseudo-history, probably an invention of the Christian writers.

The earliest surviving reference to Partholón is in the Historia Brittonum, a 9th-century British-Latin compilation attributed to Nennius. Partholon was the first colonist of Ireland by way of Greece. He is now considered just a character in medieval Irish Christian pseudo-history, probably an invention of the Christian writers.

One wonders what book Charles was getting his information from – there is a book on the history of Ireland in the catalogue, but alas! don’t know if this is what Charles is reading:

John O’Driscol. The History of Ireland. 2 vols. London, 1827. There is a chapter on “Ancient State of Ireland” – but a quick search does not bring up anything on Partholon … We care about this title however, because it is A Lost Sheep!

‘Monday December 28 … read one of Wartons Deathbed scenes, which I liked very much …’

– Warton, John. Death-bed scenes and pastoral conversations. London: John Murray, 1830.

This is exciting to see referenced in Charles’s diaries because this was found and returned to Chawton by our famed GLOSS book detectives! – and although it is not in the 1818 catalogue, it is in the 1908 Chawton catalogue and has the Montagu George Knight bookplate.

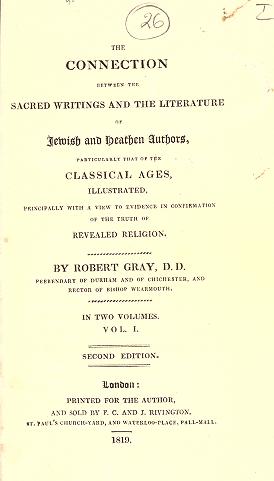

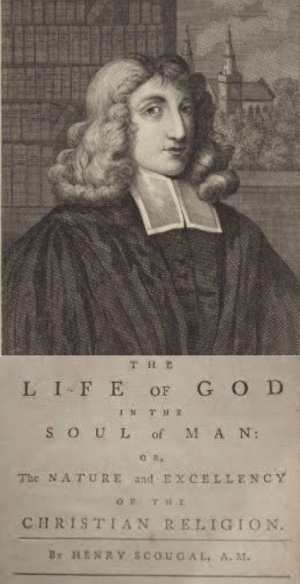

‘Wednesday Dec 30 … We are reading Scougal’s Life of God in the soul of man, & like it.’) … (‘One of the best books I ever read’ he reports on completing Scougal). I read a little of Stanley on birds in the evening.’

‘Wednesday Dec 30 … We are reading Scougal’s Life of God in the soul of man, & like it.’) … (‘One of the best books I ever read’ he reports on completing Scougal). I read a little of Stanley on birds in the evening.’

– Henry Scougal. The Life of God in the Soul of Man: or, the Nature and Excellency of the Christian Religion. With Nine other Discourses on important Subjects. By Henry Scougal, A. M. and S. T. P. The Second Edition. To which is Added, A Sermon Preached at his Funeral, by G. G. D. D. London, 1735.

You can read more on Scougal and a summary of his book here. This is in the GPL catalogue and in the Knight Collection: and lots of writing in these volumes – done by Charles?? one can wonder! (Love this “Amen!!!)

Stanley on birds must refer to Edward Stanley’s A Familiar History of Birds: Their Nature, Habits, and Instincts. First published in 1835, this is not in the catalogue and may have been Charles’s own personal copy.

I’ll finish with these two last jottings in Charles’s Diary no. 9:

‘Jany 2d (1836) I read some of D Israelis curiosities of literature before dinner.’

– Isaac D’Israeli. Curiosities of literature. 7th ed, corrected. In five volumes. London: John Murray, 1823. Vols. 3-5 are in the Knight Collection (not yet on the RwA website).

– Isaac D’Israeli. Curiosities of literature. 7th ed, corrected. In five volumes. London: John Murray, 1823. Vols. 3-5 are in the Knight Collection (not yet on the RwA website).

Finally a little lighter reading for Charles! The “Curiosities” is a collection of anecdotes about historical persons and events, unusual books, and the habits of book-collectors. It was very popular and remained in print through many editions. D’Israeli’s other claim to fame is that he was the father of Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli.

‘Jany 10 … contrived to spin out my toilet with a little of Nelson’s devotions till 9 our breakfast hour.’

‘Jany 10 … contrived to spin out my toilet with a little of Nelson’s devotions till 9 our breakfast hour.’

– Nelson, Robert. The Practice of True Devotion, In Relation to the End, as well as the Means of Religion; With an Office for the Holy Communion. By Robert Nelson, Esqr; 14th ed. To which is added The Character of the Author. London, 1758.

This is in the 1818 catalogue but is not in the collection, so we end with A Lost Sheep!

*****

More to come with Charles’s Diaries … another long list, so stay tuned. And with many thanks again to Hazel Jones for all these library references.

c2019 Reading with Austen blog

Charles Bridges was born March 11, 1803 at Godmersham Park in Kent, the 8th child of Jane Austen’s brother Edward Knight and Elizabeth Bridges. He was a commoner at Winchester* from 1816-1820, attended Trinity College, Cambridge and was ordained in 1828. He was the curate of West Worldham in Hampshire and rector of Chawton from 1837-1867. He died unmarried on October 13, 1867, aged 64 years. He is buried in the graveyard at the St. Nicholas Churchyard in Chawton (Section B: Row 2. 70 ).

Charles Bridges was born March 11, 1803 at Godmersham Park in Kent, the 8th child of Jane Austen’s brother Edward Knight and Elizabeth Bridges. He was a commoner at Winchester* from 1816-1820, attended Trinity College, Cambridge and was ordained in 1828. He was the curate of West Worldham in Hampshire and rector of Chawton from 1837-1867. He died unmarried on October 13, 1867, aged 64 years. He is buried in the graveyard at the St. Nicholas Churchyard in Chawton (Section B: Row 2. 70 ).

This is a continuation of recording the diaries of Charles Bridges Knight, son of Edward Knight, and his mentions of the books he is reading in the Godmersham Park Library. We thank Austen scholar Hazel Jones for so graciously sharing her finds with us. It very much brings this library to life as we imagine Charles sitting and reading there, much like his aunt Jane Austen would have done several years before. Some of his diary entries are about the Library itself – fires and warmth (or lack thereof), pictures, outside trees, etc., which brings us vividly back to Austen’s own comments of being there: “Mistress of all I survey…”

This is a continuation of recording the diaries of Charles Bridges Knight, son of Edward Knight, and his mentions of the books he is reading in the Godmersham Park Library. We thank Austen scholar Hazel Jones for so graciously sharing her finds with us. It very much brings this library to life as we imagine Charles sitting and reading there, much like his aunt Jane Austen would have done several years before. Some of his diary entries are about the Library itself – fires and warmth (or lack thereof), pictures, outside trees, etc., which brings us vividly back to Austen’s own comments of being there: “Mistress of all I survey…”

Laurence Echard. A General Ecclesiastical History from the Nativity of our Blessed Saviour to The First Establishment of Christianity By Humane Laws, Under the Emperour Constantine the Great. Containing the Space of about 313 Years. With so much of the Jewish and Roman History as is Necessary and Convenient to illustrate the Work. To which is added, A Large Chronological Table of all the Roman and Ecclesiastical Affairs, included in the same Period of TIme. By Laurence Echard, A. M. Prebendary of Lincoln, and Chaplain to the Right Reverend James, Lord Bishop of that Diocese. London, 1702.

Laurence Echard. A General Ecclesiastical History from the Nativity of our Blessed Saviour to The First Establishment of Christianity By Humane Laws, Under the Emperour Constantine the Great. Containing the Space of about 313 Years. With so much of the Jewish and Roman History as is Necessary and Convenient to illustrate the Work. To which is added, A Large Chronological Table of all the Roman and Ecclesiastical Affairs, included in the same Period of TIme. By Laurence Echard, A. M. Prebendary of Lincoln, and Chaplain to the Right Reverend James, Lord Bishop of that Diocese. London, 1702. Thomas Knight bookplate and this interesting cover: this Elizabeth Knight is the original cousin with the Knight name which was taken by Thomas Brodnax May in order to inherit the estate in Chawton. It was his son Thomas who adopted Jane Austen’s brother. For a full understanding of all these names see Chawton Manor and Its Owners; A Family History, by William Austen-Leigh and Montagu George Knight.

Thomas Knight bookplate and this interesting cover: this Elizabeth Knight is the original cousin with the Knight name which was taken by Thomas Brodnax May in order to inherit the estate in Chawton. It was his son Thomas who adopted Jane Austen’s brother. For a full understanding of all these names see Chawton Manor and Its Owners; A Family History, by William Austen-Leigh and Montagu George Knight. Robert Gray: The Connection between the Sacred Writings and the Literature of Jewish and Heathen Authors, particularly that of the Classical Ages, Illustrated, principally with a view to evidence in confirmation of the truth of Revealed Religion. By Robert Gray, D. D. Prebendary of Durham and of Chichester, and Rector of Bishop Wearmouth. [Later the Bishop of Bristol], published in London in 1816 – in the 1818 catalogue and

Robert Gray: The Connection between the Sacred Writings and the Literature of Jewish and Heathen Authors, particularly that of the Classical Ages, Illustrated, principally with a view to evidence in confirmation of the truth of Revealed Religion. By Robert Gray, D. D. Prebendary of Durham and of Chichester, and Rector of Bishop Wearmouth. [Later the Bishop of Bristol], published in London in 1816 – in the 1818 catalogue and

The earliest surviving reference to Partholón is in the Historia Brittonum, a 9th-century British-Latin compilation attributed to Nennius. Partholon was the first colonist of Ireland by way of Greece. He is now considered just a character in medieval Irish Christian pseudo-history, probably an invention of the Christian writers.

The earliest surviving reference to Partholón is in the Historia Brittonum, a 9th-century British-Latin compilation attributed to Nennius. Partholon was the first colonist of Ireland by way of Greece. He is now considered just a character in medieval Irish Christian pseudo-history, probably an invention of the Christian writers. ‘Wednesday Dec 30 … We are reading Scougal’s Life of God in the soul of man, & like it.’) … (‘One of the best books I ever read’ he reports on completing Scougal). I read a little of Stanley on birds in the evening.’

‘Wednesday Dec 30 … We are reading Scougal’s Life of God in the soul of man, & like it.’) … (‘One of the best books I ever read’ he reports on completing Scougal). I read a little of Stanley on birds in the evening.’

– Isaac D’Israeli. Curiosities of literature. 7th ed, corrected. In five volumes. London: John Murray, 1823. Vols. 3-5 are in the Knight Collection (not yet on the RwA website).

– Isaac D’Israeli. Curiosities of literature. 7th ed, corrected. In five volumes. London: John Murray, 1823. Vols. 3-5 are in the Knight Collection (not yet on the RwA website). ‘Jany 10 … contrived to spin out my toilet with a little of Nelson’s devotions till 9 our breakfast hour.’

‘Jany 10 … contrived to spin out my toilet with a little of Nelson’s devotions till 9 our breakfast hour.’

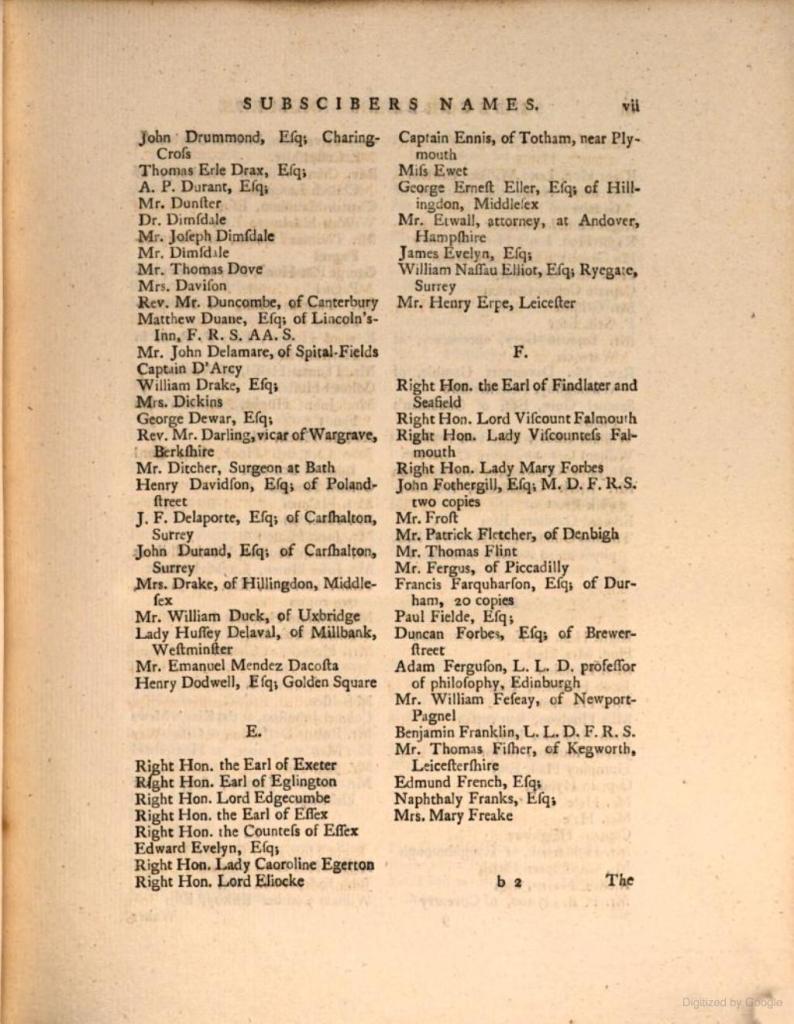

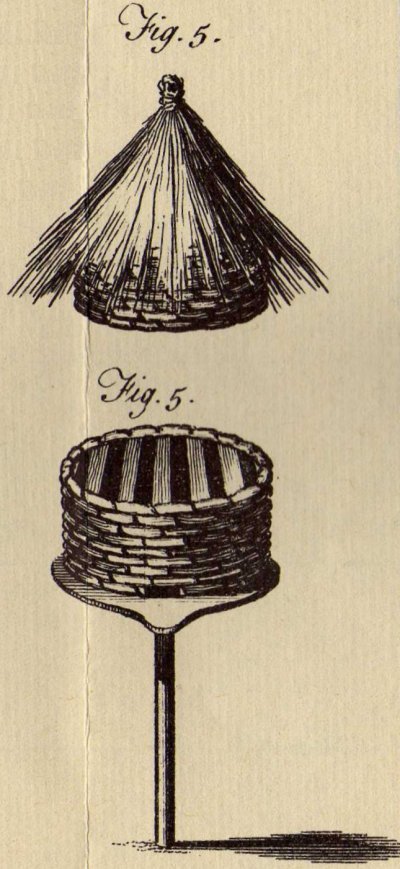

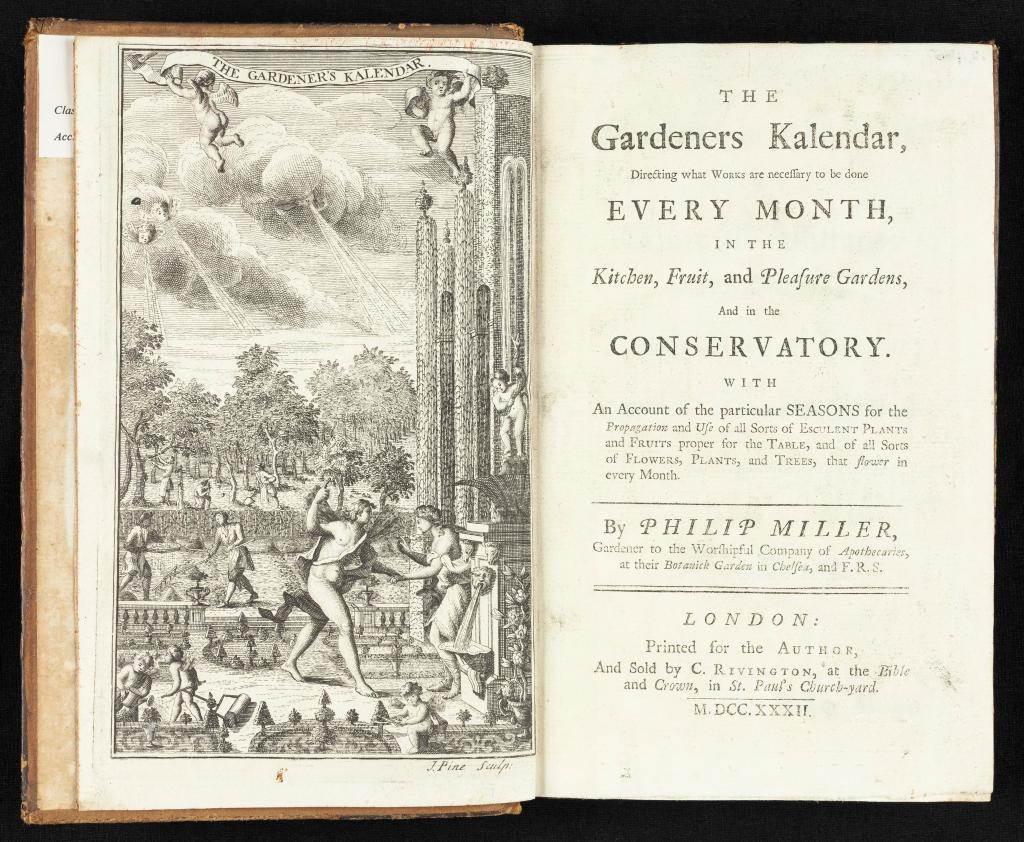

Willughby, Francis. The Ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the County of Warwick Esq; Fellow of the Royal Society. In Three Books. Wherein All the Birds Hitherto Known, Being reduced into a Method sutable [sic] to their Natures, are accurately described. The Descriptions illustrated by most Elegant Figures, nearly resembling the live Birds, Engraven in LCCVIII Copper Plates. Translated into English, and enlarged with many Additions throughout the whole Work: To which are added, Three Considerable Discourses, I. Of the Art of Fowling: With a Description of several Nets in two large Copper Plates. II. Of the Ordering of Singing Birds. III. Of Falconry. By John Ray, Fellow of the Royal Society. [Epigraph on title page]. London: Printed by A.C. for John Martyn, Printer to the Royal Society, at the Bell in St. Pauls Church-Yard, 1678.

Willughby, Francis. The Ornithology of Francis Willughby of Middleton in the County of Warwick Esq; Fellow of the Royal Society. In Three Books. Wherein All the Birds Hitherto Known, Being reduced into a Method sutable [sic] to their Natures, are accurately described. The Descriptions illustrated by most Elegant Figures, nearly resembling the live Birds, Engraven in LCCVIII Copper Plates. Translated into English, and enlarged with many Additions throughout the whole Work: To which are added, Three Considerable Discourses, I. Of the Art of Fowling: With a Description of several Nets in two large Copper Plates. II. Of the Ordering of Singing Birds. III. Of Falconry. By John Ray, Fellow of the Royal Society. [Epigraph on title page]. London: Printed by A.C. for John Martyn, Printer to the Royal Society, at the Bell in St. Pauls Church-Yard, 1678.

*Hazel Jones is the author of Jane Austen & Marriage (Bloomsbury Continuum 2009, Uppercross Press 2017), Celebrating Pride & Prejudice (co-authored with Maggie Lane, Lansdown 2012), Jane Austen’s Journeys (Hale 2014) and is currently writing a book on Jane Austen’s Knight nephews. She was a tutor in the Department of Lifelong Learning at Exeter University until 2005 and continues to teach residential courses on aspects of Jane Austen’s writing, life and times. She is the membership secretary and a co-founder of the UK Jane Austen Society, South West Branch.

*Hazel Jones is the author of Jane Austen & Marriage (Bloomsbury Continuum 2009, Uppercross Press 2017), Celebrating Pride & Prejudice (co-authored with Maggie Lane, Lansdown 2012), Jane Austen’s Journeys (Hale 2014) and is currently writing a book on Jane Austen’s Knight nephews. She was a tutor in the Department of Lifelong Learning at Exeter University until 2005 and continues to teach residential courses on aspects of Jane Austen’s writing, life and times. She is the membership secretary and a co-founder of the UK Jane Austen Society, South West Branch.

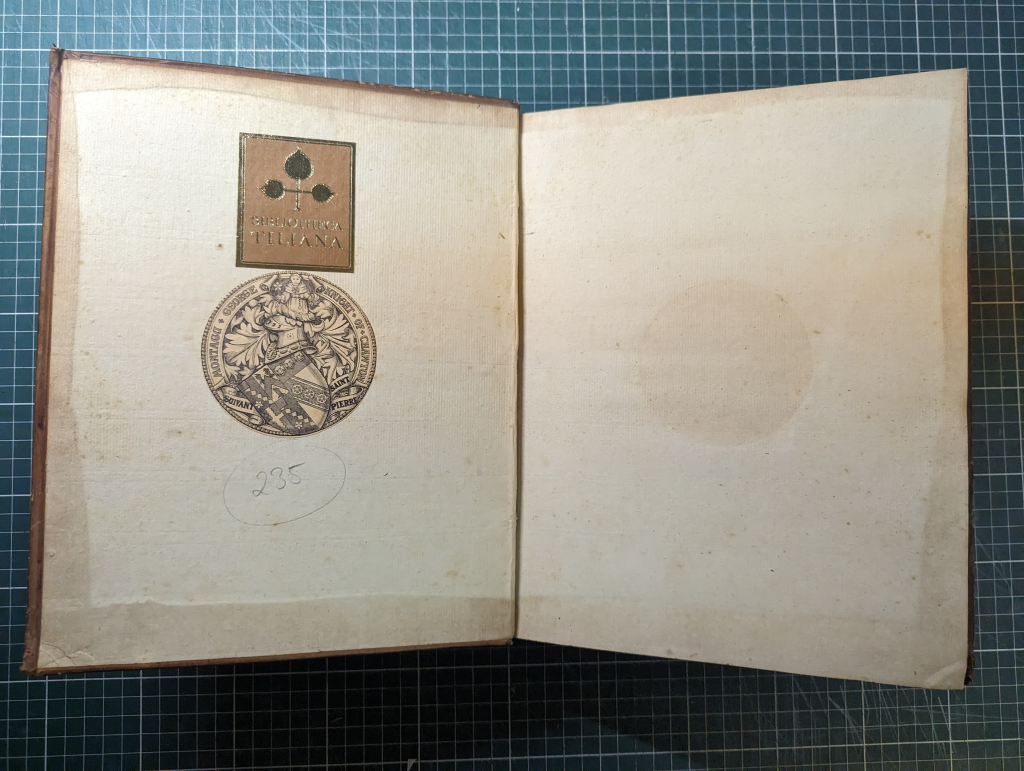

[CHL book with bookplate and shelf ticket]

[CHL book with bookplate and shelf ticket]